To end homelessness, there is an urgent need for more housing that provides people on low incomes with security, decent living conditions and affordable rents. The decline in availability of homes affordable to low income households has significantly contributed to the rise of homelessness. To stop this, housing and welfare policies must work effectively together. More homes must be built and made available at social rent levels. And more must be done to ensure that private tenancies provide the stability that people need to prevent and move on from homelessness.

Increasing the availability of decent housing, affordable to people on low incomes, is critical to successfully ending homelessness in Great Britain.

The output of new homes across all tenures has fallen short of the number required for many years across the UK. This is illustrated below:

Number of new homes required per annum and provided (position in 2016/17)

Nation - England

Nation - Scotland

Nation - Wales

(Source UK Housing Review)

*The scale of requirement to address backlog of need is higher. The Housing White paper suggests the requirement may be 275,000 homes a year or more, and the 2017 budget set a target of 300,000 homes a year by the end of the current parliament.

The Westminster Government has set a housebuilding target of 300,000 homes a year for England by the end of the current parliament. The Chartered Institute of Housing (CIH) estimates that over the five years since 2011, the cumulative shortfall between the number of homes built in England and the number needed is 370,000.

Gross housing undersupply is an acute problem across all three nations, but attention must also focus on housing affordability and type, and where homes are needed.

The number of concealed and sharing households has risen over the last decade. Sharing accommodation has become an established way of responding to housing shortage, particularly in London.

And, as fewer people can afford to buy homes, and there are fewer social rented tenancies, more people are renting their homes from private landlords. The proportion of people living in the private rented sector is higher in England (20%) than Scotland (15%) and Wales (15%), but is growing across Great Britain.

In all three countries, the need and demand for low-rent housing outstrips supply. This means there has been growing reliance on expensive and sometimes unsuitable temporary accommodation (see Chapter 7 ‘Rapid rehousing’). Many homeless people are being helped to access private tenancies to provide settled housing.

England

During 2015/16, more than 90,000 households were helped to find mainstream housing under homelessness prevention and relief measures and the main homelessness duty. Around one third were provided with a private tenancy. The rest entered social housing with the exception of a few hundred households able to afford low-cost home ownership.

Private renting also provides ‘move-on’ housing for a significant proportion of people moving on from homelessness hostels and others outside the statutory homelessness framework. Around ten per cent of people moving on from homeless hostels moved to a private tenancy in 2015/16.13

Wales

In Wales, 38 per cent of the 8,880 households, obtained a private tenancy under the prevention and relief duty in 2016/17.

Scotland

In Scotland, of the 22,245 unintentionally homeless households, or those threatened with homelessness, six per cent were helped into private rented sector settled housing. There is significant local variation, however. In Edinburgh, 21 per cent obtained settled private rented housing.

Private rented housing can provide a sustainable housing option for people moving on from homelessness.16 But many homeless people struggle to get access to homes let by private landlords and the sector is often not fit for purpose.

In all three nations, increased reliance on private renting means people are spending more of their income on rent. They are more likely to be pushed into poverty by the high cost of housing relative to earnings. A higher proportion of private renters of working age spend more than a third of their incomes on housing than working-age adults living in other tenures (see figure 11.1).

*SEE FIGURE 11.1 WORKING-AGE ADULTS SPENDING MORE THAN A THIRD OF THEIR INCOME ON HOUSING BY TENURE*

The number of people living in poverty in the private rented sector in the UK has nearly doubled in the past decade. In 2015/16 4.7 million people were living in poverty in the sector, three million of whom were in working households.

Four fifths of low income working age households living in the private rented sector spend more than one third of their net income on housing costs. This is compared with just over half of those in the social rented sector. Elements of welfare reform, particularly the widening gap between Local Housing Allowance rates and market rents, has made the sector increasingly unaffordable. It has left private renters vulnerable to rent arrears and eviction. See Chapter 10 ‘Making welfare work’.

In all three nations, the condition of housing in the private rented sector is worse than in other tenures.23 Poor conditions tend to be concentrated at the lower-cost end of the private market, and so particularly affect homeless people.

In Scotland and Wales, private landlords are obliged to join national registration schemes, but in England the private rented sector is largely unregulated.

In areas of highest housing pressure, reliance on private renting also creates opportunities for exploitation. People with the least purchasing power may be pushed into accepting very poor quality accommodation. Disreputable landlords may more readily exploit the situation, letting unsafe or overcrowded homes to people who have no choice.

Tenants are often reluctant to refer problems to their local authorities, or are unaware of their right to do so. This makes it very difficult to identify and enforce against rogue landlords. Furthermore, local authorities often struggle to tackle poor conditions and standards in the sector because of a lack of resources and poor quality data on private renting.

Local authority environmental health teams are significantly under resourced. Average budgets allocated to environmental health services per head of the population in the UK fell by eight per cent between 2010 and 2012; 1,272 jobs were lost in environmental health offices.

There is a lack of available data on landlords and the properties they let, particularly in England where there is no national register of landlords. This makes it very difficult for local authorities to effectively target enforcement work or educational training and resources at amateur and accidental landlords. More than three quarters of landlords in the UK have never been a member of any trade body or held any licence or accreditation.

In England, there has been an increase in the use of ’permitted development‘ rights to deliver housing in converted office buildings (also referred to as ‘change of use’), sometimes to provide housing targeted at vulnerable people. The number of such change of use conversions has risen dramatically since the Westminster Government introduced new powers in May 2013 (applicable only to England). There were 37,000 such conversions in 2016/17.

The local planning authority has limited power to ensure these homes meet basic standards such as minimum space and adequate light and ventilation. Schemes can be of poor quality and are not subject to affordable housing obligations. There have been calls for government to reverse the 2013 reforms.

In England and Wales, the combination of reliance on short fixed-term tenancies and rising rents has made more people homeless through tenancies ending. So, while private rented tenancies often provide homeless people with settled accommodation for a period of time, they can also be the cause of repeat homelessness.

The Scottish Government has introduced changes to give private renters in Scotland greater security of tenure than in England and Wales. The Private Housing (Tenancies) (Scotland) Act (2016) introduced a new open-ended private tenancy that can only be brought to an end under specified grounds for eviction. Except where the tenant is at fault for a breach of tenancy conditions, tenants who have lived in the property for more than six months will be entitled to 84 days’ notice. This is where the landlord seeks possession on one of the specified grounds.

Reliance on the private rented sector to house homeless people and other low income households has significantly increased the cost of Housing Benefit. This is because of the higher cost of private market rents. Between 2005/06 and 2014/15, Housing Benefit spending on 1.4 million private tenancies doubled to £9.3 billion. During the same period the cost of Housing Benefit in the social rented sector rose by just over a fifth.

Investment in housing at social rent levels is an alternative approach that would see cost benefits both for the taxpayer and for low income households. Analysis by Savills compared the costs of housing 100,000 households in the private rented sector and social rented sector respectively.

The study found that the social rented sector option generated £23.9 billion savings over the long term compared with private renting. This considered the impact of upfront investment and Housing Benefit costs. Analysis by Capital Economics found that investing in 100,000 new social rent homes per annum creates a net annual surplus for national government over the long term.

Social housing still provides the main source of housing for homeless people who approach their local authority for help across all three nations. There is significant variation, however, in national policy on the provision of social housing in England, Scotland and Wales, and the extent to which homeless people can get access to it.

In all three nations, problems with the affordability of social housing make it harder for homeless people and others on very low incomes to access social housing. This also increases the risk of rent arrears and eviction for low income households living in social housing. These problems are driven in part by the impact of reduced Housing Benefit entitlements and changes associated with the introduction of Universal Credit (see Chapter 10).

England

The effects of English housing policy have significantly reduced the supply of social rented housing available to homeless people. Particularly responsible are: disinvestment from new social rent40 housing; home loss through right to buy; conversion of social rent homes to affordable rents41, and greater conditionality for social housing.

It has been argued these policies are changing the role of the social housing sector. Instead of providing a long-term housing safety net for low income households, it is becoming an ‘ambulance service’ – helping those in most acute need for short periods of time.

As part of this changing role, the Westminster Government introduced reforms enabling social landlords to offer fixed-term tenancies to new tenants instead of long-term (or lifetime) secure tenancies.44 There was, however, limited take up of this flexibility by local authorities and housing associations.

So, through The Housing and Planning Act (2016), the government introduced provisions (not yet implemented) to end the use of secure tenancies for most people.

Analysis for the Joseph Rowntree Foundation has found that at its best, social renting provides secure and affordable homes for low income households. But the same research notes the potential of the tenure to contribute to occupants’ wellbeing can be undermined by properties let in a poor state of decoration or repair.

A social rented home can provide homeless people with greater stability than the private rented sector. But it is sometimes the case that social rented housing is let in a poor state of repair or decoration, and can negatively affect homeless people. In England the former national programme to keep homes at the Decent Homes Standard has been halted. Consequently, there are concerns that the improvement in social housing stock condition delivered between 2000 and 2010 may be reversed.

In the wake of the Grenfell tragedy, the Westminster Government has announced a review of social rented housing, but the parameters of the review have not yet been clarified.

Scotland

In Scotland there is a strong commitment to grow the stock of social rented housing, supported by the abolition of right to buy. Recent evidence suggests that the Scottish Government’s ambitious delivery targets should be achievable. But, there are concerns about affordability for tenants, whether development plans will deliver the right homes in the right places, and about the future of the programme after 2021.

Wales

The Welsh Government is committed to delivering more social rented housing and preserving the existing stock with the abolition of right to buy. There is an acknowledged need to increase the pace of delivery. There are, however, concerns about the affordability of social rented housing, and the barriers faced by low income households seeking access to social renting.

Further evidence on each of these issues detailed later in this chapter.

Crisis and the National Housing Federation have commissioned Heriot-Watt University to undertake a new analysis of housing supply requirements. The evidence in this section is all based on this study.

There is currently a backlog of need of 4.75 million households across Great Britain. The majority of these households consist of those identified as in housing need using the following definition calculated through the Understanding Society survey data:

The figures in this group have been identified by measuring those households who experienced any one or more of these problems either in the current year or the previous year. This accounts for 13.8 per cent of all households in the current year (which has been used in the calculation in table 11.2) 56 or 20.9 per cent in the current or previous year.

This data set does not take account of older households with suitability needs and a further 250,000 households fall into this category and have been added to the total backlog of need.

Added to this figure are components of Heriot-Watt’s analysis on core and wider homelessness (see Chapter 5 ‘Homelessness projections’). A further 330,000 households58 are added to the total. They are comprised of those who are rough sleeping, living in cars, tents and public transport, hostels, sofa surfing, squatting, living in non-residential buildings, or living unsuitable temporary accommodation. This number also includes those leaving institutions such as prisons and hospitals, and non-permanent private renters (allowing for double counting).

Another component of the backlog of need are those households whose housing costs are unaffordable. This is even though they may not be identified in the specific needs above (ie those paying more than our norm ratios but not indicating actual immediate difficulties with payment). A broad indicator of this problem would be households in poverty ‘After Housing Costs’ on the standard UK measure of 60 per cent of the median income. This equates to 17.3 per cent of households across Great Britain. There are an additional 240,000 under-40 households living in the private rented sector (over and above those already counted as in need) who cannot afford it, according to our affordability criteria, and who should be able to access social housing. There are also another 75,000 who could afford intermediate affordable rents. The equivalent numbers from the older age groups may be of a similar order of magnitude, adding up to 0.51 million households in total.

These housing needs cannot be met instantaneously. It will take time to build up an effective housebuilding programme to address these existing needs plus expected future needs and demands. Heriot-Watt’s analysis assumes housebuilding will take place over 15 years to allow sufficient time and resources to meet the backlog of need set out belowabove. Over the 15-year period the total level of new housebuilding required is estimated at 383,000 units per year including 100,500 units per year for social rent. The list below sets out how this splits out across England, Scotland and Wales. The figure take account of the analysis of need and affordability and a balanced assessment of the range of outcomes forecast in the model. This includes regional equity, reasonable chances of rehousing for households in need, and potential issues of low demand which affect some areas, particularly Scotland.

(1) Back-log of housing need in Great Britain

3.66m households in GB have the following type of housing need/requirement:

0.33m households in GB have the following type of housing need/requirement

0.25m households in GB have the following type of housing need/requirement

0.51m households in GB have the following type of housing need/requirement

Source: G Bramley (Forthcoming) Housing supply requirements across Great Britain for low income households and homeless people. London: Crisis and the National Housing Federation

Number of new homes needed to address homelessness

As this chapter highlights, homeless people face increased barriers to accessing social housing and part of the issue is insufficient stock and new supply to meet the growing need. Heriot-Watt’s analysis shows that the net flow of households experiencing core homelessness in 2016 was 267,000 in England. The number of new social housing lets to all tenants was only 136,000, showing how much demand outstrips supply

If the suggested housebuilding scenario in the list below is achieved, by the end of the 15-year period there would be 274,000 new lettings in social housing. With a flow of 160,000 core homeless households during that year. Therefore, building a lot more social housing makes it much more possible for homeless household to be rehoused in social rented housing where this is most appropriate.59 It also contributes to a wider programme which will help to prevent and reduce homelessness by providing more housing opportunities and better affordability in the market in general.

(2) Target house-building numbers by tenure and country, 2016-31

England

Wales

Scotland

GB Total

We advocate a range of interventions to provide a sufficient supply of housing for homeless people across Great Britain. In England, this includes significantly increased national and local government investment in housing at social rent levels to meet identified housing requirements. In Scotland, it means maintaining and effectively targeting investment in the longer term to meet identified needs. In Wales, it means continuing to grow and effectively target the investment already committed.

While investment programmes are rolled out, ethically-minded private landlords and institutional investors across Great Britain should play a greater role in providing homes for homeless people. This should include provision in both the new build (build-to- rent) and buy-to-let sectors, and making effective use of private rented sector access (help to rent) schemes.

There is significant variation in house prices, affordability and development economics across each nation’s housing markets. So interventions to tackle homelessness must be shaped by local market conditions, and respond to the varying levels of what people need. They should also be underpinned by a welfare system that ensures Housing Benefit is available to meet the costs of renting in both the social and private rented sectors.

Across all three nations, the lack of affordable housing was identified as the biggest barrier to relieving homelessness in the extensive national consultation we undertook to inform this plan. Greater availability of social housing was identified as the most important resource needed to help local authorities meet the needs of people who are homeless or at risk of homelessness. This was also a key issue raised by consultation participants with lived experience of homelessness.

England

In England, there is no national target for building homes at social rent levels. Government policy since 2012 has resulted in a significant reduction in the number of homes for social rent. New build targets have instead focused on overall housing supply, and on a broadly defined category of ‘affordable homes’ that includes starter homes.

Only London has a target for the delivery of new homes at rents based on social rent levels. This follows the Mayor of London’s decision to include a funding stream for homes at rent levels equivalent to target rents for social housing. These rents are referred to as ‘London Affordable Rent’.

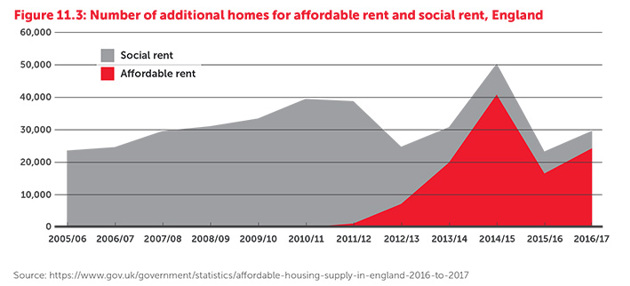

The government’s announcement of an additional £2 billion to fund delivery of up to 25,000 social rent homes over five years is welcome. However this will not make up for the decrease in provision of additional social rented homes from a high of 40,000 in 2010/11 to just 5,000 in 2016/17. And since 2012, 150,000 social rent homes have been lost through conversions to affordable rent, right to buy and demolition

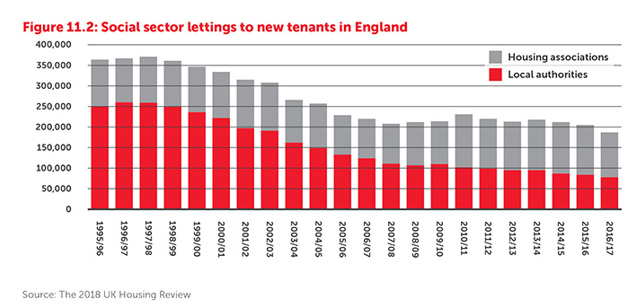

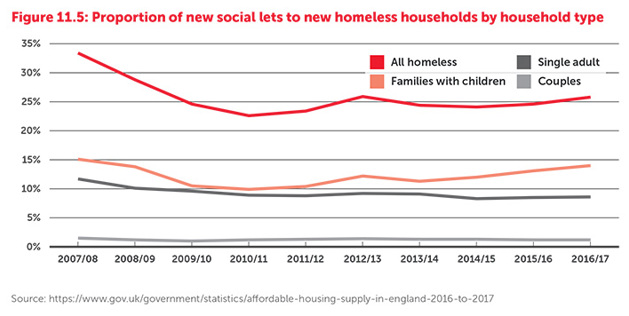

Social housing has been subject to a one per cent annual rent cut between 2016 and 2020. This reduced the amount of money available to social landlords, and as a result is estimated to have resulted in the construction of 14,000 fewer affordable homes. While local authority new build housing completions are rising, the total output was in the region of only 2,000 homes in 2016/17 (not just homes for social rent). The number of lettings to new tenants has declined over the past two decades, and the proportion of lettings to homeless people has fluctuated at around a fifth.

Increasing the supply of social rented homes in England is central to long-term planning to end homelessness. In section 11.4 we propose that the Westminster Government sets targets for and invests in substantial increases in the delivery of social rented housing. Policies that have resulted in sustained reductions in the stock of homes at social rent levels must be reversed. The barriers that further limit homeless people’s ability to access social rented housing must also be addressed

Scotland

Scotland has committed to deliver 35,000 social rented homes between 2016 and 2021. A £3 billion investment programme underpins the commitment

A 2018 review of strategic investment plans for affordable housing suggests that this target is likely to be achieved.69 It projects that 78 per cent of new affordable homes will be for social rent.

Combined with the effect of abolishing the right to buy, the same review found that this programme should produce the first significant and sustained increase in the number of socially rented homes since 1981. However, the review highlights that investment plans could be more effectively targeted to address varying local needs. In some areas the replacement of obsolete homes or refurbishment of existing stock is a greater priority than building new social rent homes. The review cautions against viewing the programme purely in terms of its capacity to deliver additional homes. The same review highlights concerns about whether the allocation of Affordable Housing Supply Programme Funds between areas in Scotland ensures the right homes are being built in the right places.

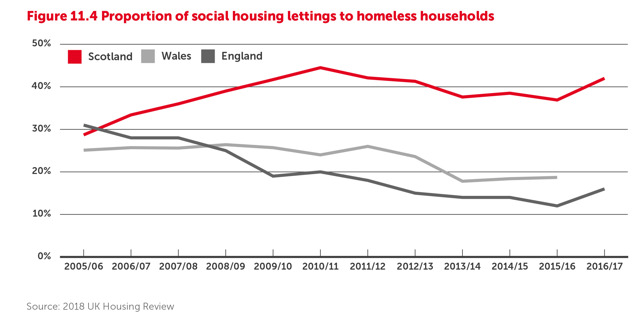

Scottish local authorities delivered around a quarter of social rent homes in the 2011-2016 programme.71 This reflects greater flexibility on borrowing and rent setting than is the case in England. Two fifths of social lettings to new tenants (40%) in Scotland were allocated to homeless people in 2016/17. This is a far higher proportion than in England or Wales. Despite this, homeless people still sometimes face affordability barriers to accessing social housing in Scotland.

Wales

In Wales £1.5 billion is allocated to deliver 20,000 new affordable homes between 2016 and 2021, of which 65 per cent will be for rent (equivalent to 2,600 homes a year). This doubles the Welsh Government’s previous 10,000 homes target which was exceeded by 15 per cent. Local authorities are likely to have a small role in delivering social rented homes. There is a target of 1,000 homes over the current Assembly term. The right to buy is being abolished in Wales, as in Scotland. Concerns have been raised, however, about the sector’s ability to meet affordable housing targets. The Welsh Government has launched an independent review to address the need for further reforms. While there is a strong policy commitment to increasing the supply of social renting in Wales, fewer than a fifth of new social lettings are to homeless people. Homeless people still face affordability barriers to accessing social housing in Wales.

All three nations also need interventions to help homeless people get access to stable, private rented tenancies. This means tackling the lack of tenure security that characterises private renting in England and Wales, and tackling poor conditions and unaffordable rent increases in all three nations.

Help to rent schemes and social lettings agencies can help increase homeless people’s access to private rented tenancies and support them in sustaining them too. More can be done to increase the role of such schemes across all three nations. More can also be done to improve homeless people’s access to private renting in both the buy to let market and the emerging build to rent sector – particularly socially-minded versions of this.

We include proposals on these issues later in the chapter.

What needs to be done to increase the availability of housing for homeless people varies in different housing markets in each nation.

The Commission for Housing in the North (of England) highlights the need for investment to restructure housing that is no longer fit for purpose in underperforming and unpopular areas.

Crisis services operating in the Midlands, the North of England and in parts of Scotland and Wales report that while it is possible for single homeless people to access social rented housing, it can be in locations that make it hard for people to find and get to work or training. Aligning housing investment programmes with employment, industrial and transport strategies is essential to underpin national and local strategies to tackle homelessness.

Increasing affordable housing supply – the wider solutions

Wider solutions to the problem of too few homes provide the context for our recommendations on housing solutions to homelessness. It is not within the scope of the plan to recommend wider land supply, planning and housing investment reforms. However, it is clear that such reforms are essential to increase the supply of affordable homes.

This section of the plan highlights four key areas where reform is needed.

Increasing the supply of land for affordable housing

Housing providers from all three nations participating in a roundtable discussion convened by Crisis to inform this plan, said the operation of the land market is a significant barrier to more affordable housing provision.78 In England and Wales this is caused by the way that both private and public land are brought forward for development.

Private land

Landowners typically hold out for the highest price for their land. The current system enables developers to pay more for land by reducing other costs. For example, they can reduce the size of homes or the amount of affordable housing

This creates a vicious cycle. Landowners’ expectations of a high sales price, sometimes referred to as ’hope value‘, have tended to drive up land values and drive down build quality, space standards, infrastructure contributions and the contribution that market-led development makes to the delivery of affordable homes.80 It also means higher affordable housing grant rates are needed to meet rising land costs.

Shelter and others have called for reforms to make land available on a larger scale and at lower values to deliver genuinely affordable housing. Proposed reforms include introducing a fairer way of valuing land for housing development, and making greater use of development corporations and compulsory purchase powers to deliver new homes.

The ‘New Civic Housebuilding’ proposals developed by Shelter provide a model for reform.82 They use the successes from historic examples such as the original Garden City model. Community Land Trusts (CLTs) can also hold the value of land for the benefit of the community, and enable the delivery of affordable homes and workspaces.

Public land

Housing providers have called for better use of public land to enable affordable housing. But pressures on budgets mean local authorities and other public bodies can be less inclined to accept lower land values in return for more affordable homes.

The CIH is among those urging public bodies to allow sale of land at less than full market value to deliver affordable homes. It also calls on government to broaden the scope of what can determine ’best consideration‘ for land sales, where this will provide affordable housing.

Local authorities are also being encouraged to adopt the best practice of exemplar local authorities, and be more active in assembling sites and commissioning masterplans, and using compulsory purchase order powers to do so.

In Scotland, land supply is considered a key risk to the achievement of the government’s ambitious affordable housing targets. Council-owned land plays a major role in affordable housing delivery – but there are concerns that the supply pipeline is short-term.

As in England and Wales, there are issues around landowners’ expectations being out of line with market prices, resulting in sites being held back. Scottish local authorities are also relying more heavily on developer contributions to deliver affordable housing. There are concerns about the potential impact of market volatility on the rate at which new homes are built.

Maximising developer contributions to affordable housing

The planning system allows local authorities to seek a proportion of affordable homes on new housing developments through legal agreements. These are known as section 106 agreements in England and Wales and section 75 agreements in Scotland.

The effectiveness of section 106 in delivering affordable housing has been undermined in part by changes to the English National Planning Policy Framework in 2012.

Between 2007/08 and 2011/12, section 106 delivered an average of 27,000 affordable homes a year. But between 2012/13 and 2015/16, after changes to the planning system, this fell to an average of 17,000 homes.

The Westminster Government has been urged to close what Shelter has called the ’viability loophole’.95 This is the process where developers argue that they cannot deliver the amount of affordable housing stipulated in local planning policies because their costs (including land price) do not allow enough profit.

Under the current interpretation of planning policy, higher land costs squeeze out provision for affordable housing. Associated concerns include that developers’ profit assumptions have risen from a typical 14 per cent before the 2008 crash to 20 per cent. These assessments are often not available for public scrutiny.

A growing proportion of new housing development in England has been delivered by converting commercial buildings for residential use; 17 per cent of additional homes in 2016/17. In England, these schemes are not subject to section 106 requirements. This further undermines new developments’ contributions to meeting affordable housing need.

National governments in England and Wales have acknowledged weaknesses with the section 106 process and are developing proposals to address them. There are concerns, however, that the Westminster Government’s reform measures do not provide local planning authorities with the tools to ensure section 106 obligations can always be enforced.

In Wales, the role of developer contributions will be addressed through an independent review examining changes needed to increase affordable housing supply in Wales.

Concerns have also been raised about increased reliance on section 75 contributions to meet affordable housing need in Scotland. Plans for reform are being considered alongside the introduction of a new infrastructure levy (see text box – ‘National government strategies to tackle housing undersupply’).

Diversifying housing delivery to increase supply

Governments in all three nations have acknowledged the need to increase the range of types of agency involved in building new homes to boost housing supply.

Governments are also exploring the use of new ways of building housing – for example using ‘Modern Methods of Construction’ (MMC) – to help increase the number of homes built each year. We look at the likely impact of these approaches on the supply of homes for homeless people and other low income households below.

Local authority house building

Until the late 1970s local authorities had a much more significant role in house building. They regularly built around 100,000 homes a year. Changes in policy and funding in the 1980s meant a dramatic fall in local authority house building. While councils are starting to build more homes again, the scale of delivery is very limited.

In England there have been calls for caps on local authority borrowing to be lifted to enable them to build more homes for social rent.Because of the caps, many English local authorities have established local housing companies and partnerships enabling them to build homes outside the borrowing restrictions that restrict the construction of social rented homes. Some local housing companies buy property on the open market and provide homes for private rent.

There is evidence that some local housing companies are delivering a small proportion of new homes at social rent (or broadly equivalent) levels aimed at homeless people and others on the lowest incomes. But the same evidence suggests that schemes more often provide intermediate or market rent homes aimed at people on median earnings or above. Some have expressed concerns that local housing companies use up council land that might have produced 100 per cent social rented housing if used in other ways.

The emerging local housing company sector is thought to be capable at present of delivering an additional 2,000-3,000 homes (of all tenures) per annum.105 It may have the capacity to increase this to an additional 25,000 homes over five years.

Housing associations participating in a roundtable discussion informing this plan, raised concerns that local authorities and development companies are increasingly ‘land banking’ – holding on to – the types of sites once available to them. We were told it is becoming harder for housing associations and charities who provide homes directly for homeless people and others on low incomes to get access to land.

In Wales, local authorities have built very few homes in recent years, but output is expected to grow, with councils committing to deliver 1,000 affordable homes over the current Assembly term.

In Scotland, local authorities have a more significant role in providing affordable housing; and they have built around 1,000 new homes in each of the past five years.

Housing association delivery of homes for market rent and sale

Wider changes in practice are also altering the profile of housing development, including increased involvement by housing associations in providing housing for sale and rent. Housing associations are now providing homes for market rent, homes for sub-market rents without government funding, and intermediate rental homes funded through affordable housing programmes.

People targeted for sub-market rent homes are those who cannot afford to rent at usual market rents, but are unlikely to qualify for social housing.Research suggests that housing association (and local authority) involvement in market renting can help raise standards in the private rented sector, and generate a source of funding – a cross subsidy – for social renting. But overall it has had a limited direct impact in increasing the supply of homes affordable to homeless people.

Build to rent

Across the UK there are around 19,000 build to rent homes. A further 27,500 are under construction; there are also 8,500 planning permissions. Housing associations are among the largest developers of build to rent housing in England. In 2017, the Scottish Government launched a Rental Income Guarantee to support increased investment in build to rent housing.

The management arrangements typical of build to rent schemes mean that all tenants can receive the same level of service regardless of whether they live in market or affordable rent homes. This means genuinely mixed income communities can be created using a cross subsidy model.

However, build to rent developments are not typically required to provide housing for the lowest earners. Also, even though they are classed as ‘affordable’, tenants are still expected to meet the standard market requirements for deposits and rent in advance. This means build to rent homes are less accessible to households on the lowest earnings, and are unlikely to be available to households moving on from homelessness.

A build to rent example intended to offer affordable housing for people who may need Housing Benefit to meet the cost of their rent is described below

Chesterfield House, Wembley, London Borough of Brent

This build to rent scheme will provide 239 homes to be completed by 2019. In addition to homes at market rents, the scheme will provide 35 homes at 80 per cent market rent and 33 at Local Housing Allowance rate (or 70 per cent market rent), whichever is the lower. The section 106 agreement for the site sets out options for the management of the Local Housing Allowance rate housing. This includes an option that the local authority nominates households to the Local Housing Allowance rate homes to enable it to discharge its statutory housing duties into the dwellings in perpetuity.

Community-led housing

The community-led sector has potential to provide housing solutions for homeless people.

Community-led housing Community-led housing describes housing that meets the needs of a local community or group of people. It is commissioned, built, owned or managed by residents themselves or by a not-for-profit agency representing residents or the wider local community. This broad definition can include the following.

In Scotland, community-led may also typically refer to community-led housing associations.

Community-led housing has expanded over the last decade and delivers around 400 additional homes a year in England. The Smith Institute’s review of community-led provision noted the benefits of involving local people to produce homes and neighbourhoods marked by quality, innovation and sustainability.

There are 225 CLTs providing around 532 homes in England and Wales, with plans to develop 3,000 homes by 2020.121 The Smith Institute analysis found that in England, co-housing and self-help groups provide around 3,000 homes. The number of homes owned by housing co-operatives is far greater, at around 170,000.

Scotland has a well-established cooperative housing network. National government funding is available for affordable homes delivered by community-led organisations. The Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act (2015) provides communities with rights to acquire and develop land.

The Welsh Government has sought to encourage the growth of housing co-operatives. It provides funding to support ‘pioneer’ schemes.

The Westminster Government also makes funding available to support the expansion of the community-led housing sector. There have been calls for existing programmes of government support for community-led housing to be expanded to encourage more CLTs in urban areas.

Modern Methods of Construction (MMC)

National governments are also responding to calls to increase the role of MMC. This housing production approach seeks to rapidly increase supply through technical innovations that can improve the form, quality and sustainability of new housing. The potential role of MMC to boost supply has been recognised for some time; there are examples of MMC construction delivering good quality homes for homeless people. Models such as Y-cube (see below) offer scope to increase the pace of housing delivery targeted at low income households and homeless people. Where relevant it can be an effective way of bringing small and temporary130 sites into use

Y-cube 131 Developed by Architects Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners, the YMCA and Aecom, Y-cube was piloted in the London Borough of Merton. The scheme provides self-contained one-bedroom flats for 36 people nominated by YMCA and Merton Council with rents at 65 per cent of local market rates. The build cost was £33,000 per cube to deliver a 26sqm internal living space; with on-site costs the total build price was £50,000. The construction period was 5.5 months. The properties have a life of 60 years; long enough for use as permanent housing. They can also be moved, providing opportunities to use them as an interim housing solution on temporary sites.

The Y-cube development provided self-contained flats smaller than the Westminster Government’s nationally described space standards for one-bedroom flats. This was considered justifiable on a variety of grounds relating to the quality of the development.

But it is important to distinguish between such developments and smaller, unsuitable housing models – such as homes made from shipping containers, sheds, or poor quality conversions. The Y-cube is built to standards suitable for permanent housing of any tenure, achieving high energy efficiency and design quality. Innovative construction techniques can play a part in increasing housing supply. But housing expectations and standards must not be lowered for homeless people.

Making use of empty or obsolete homes and other buildings

Initiatives that bring empty homes and obsolete buildings back into use as affordable housing can help tackle homelessness.Tackling the empty homes issue will not solve the housing undersupply crisis But it can help meet local housing needs and improve housing conditions in some neighbourhoods, and create training and employment opportunities for homeless people.

England

There are 205,000 long-term (more than six months) empty homes in England. This is around 0.85 per cent of all homes in the country. The highest proportions of empty homes are in North East (1.4%) and North West (1.2%) England. The Empty Homes Agency in England estimates the cost of refurbishing an empty home to be between £6,000-£25,000.

Unlike Scotland and Wales there is currently no dedicated funding programme to support the creation of affordable housing from long-term empty homes. However, the 2017 autumn budget enabled local authorities to increase the council tax premium they can charge on empty homes from 50 per cent to 100 per cent.

The English Empty Homes Agency has made the case for a dedicated funding stream and supporting national strategy to bring empty and obsolete homes back into use. They also call for more innovation at local level to achieve this,135 and for grants to enable homes to be made available to homeless people.

Scotland

In Scotland, there are an estimated 37,000 long-term empty homes.136 Since 2010, the Scottish Government has funded a partnership with Shelter Scotland to help local authorities work with owners of empty homes. The partnership has brought nearly 2,500 homes back into use so far.

The Empty Homes Partnership recommends the expansion of services so that all Scottish local authorities provide a holistic empty homes service. This should include advice and information, financial support, and, as a last resort, enforcement. Nineteen councils have empty homes officers who take on these roles. The Partnership also recommends a compulsory sale order power for vacant and derelict land and buildings. This would allow local authorities to put a long-term empty property or piece of land on the open market, if it has not been used in three years and has no prospect of reuse.

Wales

In Wales, there are 23,000 empty homes, of which 1,347 (5.8%) were brought back into use in 2016/17, but with wide variation in council performance. The government has a target of bringing 5,000 homes back into use and provides £30 million to fund the Houses into Homes scheme.

External evaluation of the first three years of Houses into Homes found that it increased local government commitment to tackling the problem of empty homes, increased staffing to deal with the issue, and brought more properties back into use.But it also noted that take-up of the scheme needs to be extended to benefit more local authority areas.

National governments in England Scotland, and Wales want to tackle the causes of housing undersupply.

England

The government published its White Paper, Fixing our Broken Housing Market in February 2017. It set out proposals to increase the supply of housing and, in the longer-term, create a more efficient housing market. This followed the creation of a new National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) in 2012. The paper acknowledges a range of housing supply options are needed to meet the needs and aspirations of all households, and to support economic prosperity. The proposals focus on the following.

1 Reforms to the planning system

2 Measures aimed at increasing the pace of housing delivery

These include reforming the system of developer contributions (including the use of section 106 and the role of viability assessments). Strengthening the tools available to local authorities to speed up home building is also important. This includes encouraging use of compulsory purchase powers to support the build out of stalled sites. A new housing delivery test is also needed to ensure councils are held accountable for their role in creating enough housing. These measures are the subject of a government commissioned review led by Sir Oliver Letwin.

3 Diversifying the market

This includes enabling small and medium-sized builders to play a greater role. It also involves encouraging greater use of institutional investment to deliver new homes for private rent, supporting increased delivery by housing associations and local authorities, and encouraging an expanded role for MMC.

Since the White Paper’s publication, and in the wake of the Grenfell Tower tragedy, the government announced it will conduct a review of social housing’s role. A Green Paper is due for publication in Spring 2018. The 2017 autumn budget, confirmed that

£2 billion funding will be available to deliver social rented housing for the first time since the end of the National Affordable Housing Programme in 2010/11. The government will also raise the borrowing cap from April 2019 for specified councils in areas of high affordability by £1 billion.

Scotland

Increasing the supply of affordable homes, including social rent provision, is the main priority for Scottish housing. Recommendations to the government to sustain the affordable housing investment programme noted that land supply is a key risk to delivery.

A government commissioned independent review of the planning system in 2016,141 produced recommendations to strengthen local development plans. This involved replacing strategic development plans with an enhanced National Planning Framework.

To deliver more high-quality homes the review recommends diversifying housing delivery to meet the needs of a diverse population. This includes expanding opportunities for self-build, new build private renting, off-site construction and energy efficient housing. The Scottish Government’s response sets out proposals to implement a programme of reform.142 It is also investigating the case for land value taxation to address the rising price of land.

Wales

The Welsh Government, Welsh Local Government Association, Community Housing Cymru and the Federation of Master Builders signed a Housing Supply Pact in 2016. This addresses the changes needed to deliver an additional 20,000 affordable homes by 2021. All those involved recognise further reforms are needed to increase the pace of housing delivery, and the pact sets out the measures to be pursued. These include:

The Welsh Government has commissioned an independent review to examine the changes needed to increase affordable housing supply in Wales, with a report due in April 2019

Problem

The stock of social rented housing available to new households has declined and this means there are fewer social rented homes available to homeless people too. As noted, programmes of investment in new homes and suspending right to buy may halt or reverse recent decreases in the availability of social rent housing in Scotland and Wales. In England, however, national policy is likely to result in less social rented stock.

Across all three nations there are also concerns about social housing affordability for those on the lowest incomes, including homeless people. Continued investment in social housing is critical to tackling homelessness. But it will not, in isolation, address affordability problems for those on the very lowest incomes. This includes people who are economically inactive, those seeking work, and those in very low-paid work or with fluctuating low earnings. To tackle affordability problems, the welfare safety net must also play its part in enabling those on very low incomes to access and retain stable housing (see Chapter 10).

Scotland

The Scottish Government should maintain investment to deliver the equivalent of 5,500 homes a year at social rent levels over a 15-year period, and ensure funding is targeted effectively to meet needs identified at local housing market level.

Wales

The Welsh Government should increase its annual target for the delivery of new social rent homes to 4,000 a year, and continue to grow its investment in social rented housing to deliver the equivalent of 4,000 homes a year over a 15-year period.

Great Britain

National governments in all three nations should ensure that the rent setting framework for social rented housing in each nation delivers rents that remain affordable to those earning the National Minimum Wage and can be accessed by households in receipt of Housing Benefit.

Impact

The impact on homelessness of measures to increase the supply of social renting will depend on the extent to which available social rented homes are targeted at homeless households. Measures to increase homeless peoples’ access to social housing are the focus of the next solution: increase access to social renting for homeless people. There is a strong association between social rent supply and access for homeless people; the two must be addressed in parallel. Failure to tackle the supply shortage leaves us making the case for an increased proportion of a diminishing pool of homes, potentially to the detriment of others in housing need.

Responsibility for change

The Westminster Government must provide strategic leadership to increase the supply of social rented housing in England.

The Scottish and Welsh Governments should continue to shape programmes of investment and wider interventions to increase the output of social rented homes

Problem

Traditionally, social housing has been important in resolving homelessness. But it is becoming more difficult for homeless people to get access to social housing.

The rate and number of social housing lettings to homeless people has declined over the past decade across all three nations, though not in the last year. The overall decline is less marked in Scotland where social landlords allocated more than 40 per cent of lettings to homeless households in 2016/17 (see figure 11.4 below). This is compared with fewer than a fifth of lettings allocated in England and Wales (Welsh data is for 2015/16).

In all three nations, housing associations provide a lower proportion of lettings to homeless households than local authorities. The gap between council and housing association performance in housing homeless people is greatest in Scotland (51% councils/33% housing associations) and lowest in England (24% councils/21% housing associations). In Wales the proportions are 26 per cent councils and 14 per cent housing associations.

As illustrated earlier in this chapter, tackling the shortage of social rented housing will be critical to tackle the backlog of housing need, and the needs of homeless people. But there is evidence that other barriers are also restricting homeless people’s access to social housing.

Pre-tenancy assessment practice and the use of affordability tests

Many local authorities are concerned that homeless people are not accepted for rehousing by housing associations on affordability grounds. These concerns highlight difficulties with the operation of nominations agreements which, as noted in Chapter 13 ‘Homelessness legislation’, have been a source of complaint from both local authorities and housing associations.

Evidence from all three nations shows affordability tests and/or inflexible application by some housing providers of requirements for the first month’s rent in advance, can restrict access to social housing. There is also evidence that some housing providers adopt restrictive approaches to homeless applicants with historic rent arrears. Yet, it is sometimes the case that homeless people need rehousing exactly because of difficulties paying rent in the past. This could be because of unaffordable rents, benefit restrictions, and other circumstances outside their control.

Some social housing providers adopt practices that are sensitive to individual circumstances, and enable homeless people to gain access to social rented tenancies. This might include using pre-tenancy assessments as a way to identify measures needed to support households on very low incomes to take up a tenancy. It might also include allowing payment of a reduced sum of rent in advance or waiving the requirement while a benefit claim is resolved. The evidence presented in this chapter suggests such flexibility is not universal.

The Welsh Government Public Accounts Committee is among those raising concerns that financial assessments by social landlords may sometimes unintentionally exclude people from social housing because they are ’too poor‘. Subsequent research by Shelter Cymru found examples of applicants being unable to take up tenancies due to requirements for payment of the first month’s rent. In Scotland, registered providers are obliged to comply with a local authority’s request to provide accommodation for homeless households unless there is a ‘good reason’ not to. In practice the extent to which lettings are made available for homeless nominees varies significantly by local authority area.

Access to tenancy-related support for homeless people in general needs housing

In England, reduced spending on tenancy sustainment support can be a barrier to social housing. Local authority housing teams report social landlords’ increased reluctance to accept tenants considered to have support needs. Supporting People services have traditionally funded a range of homelessness prevention and tenancy support services. These help people access and keep their tenancies, and reassure social landlords in the process. Funding for the Supporting People programme in England has decreased by 67 per cent in real terms since 2010.

The most recent Homelessness Monitor: Wales 2017 noted that Supporting People funds have been relatively protected in Wales; unlike in England they remain ring-fenced for the time being. The Welsh Government has, however, announced plans to merge Supporting People funding with other non-housing grant funding from 2019/20. This raises significant concerns about the erosion of much-needed support for homeless people.

As noted in Chapter 13, in Scotland local authorities have a statutory duty to assess the housing support needs of unintentionally homeless applicants. They must also ensure support is provided to those assessed as being in need.

Data on homeless households’ support needs in England and Wales are hard to source. In Scotland data on the support needs of homeless applicants are gathered as part of the homelessness application process. Although there are concerns about the fluctuations in the level of need recorded by Scottish local authorities. In 2016/17, 44 per cent of those threatened with homelessness in Scotland were identified as having support needs.

Crisis has analysed the scale of support needs among working age single homeless households in England. This analysis estimates that around a third have no support needs or require access only to practical support in the early stages of their tenancy. We also estimate that a third have moderate support needs, and a third have complex or multiple support needs.

Research published in 2008 by the Centre for Housing Policy at the University of York, draws on surveys of homeless households in England. It suggests that the extent of support needs among homeless families with children is lower than the level identified by Crisis for single adult households.

Research for a consortium of housing associations has shown that effective in-tenancy support has good results. It can help tenants in mainstream housing manage their low incomes and financial difficulties, sustain their tenancies, and prevent homelessness from rent arrears. Cuts to Supporting People services in mainstream housing could limit homeless people’s prospects of both gaining and retaining access to general needs social housing.

In Chapter 13 we make the case for an extension of duties to assess support needs and provide support for homeless people in England and Wales.

Housing register eligibility in England

Changes to housing register eligibility in England, permitted by The Localism Act (2011), have also affected homeless people entering social housing. This is because the Act allows local authorities to exclude groups of people designated as ’non-qualifying‘ from housing registers.

The stated aim of the new allocations powers in The Localism Act (2011) was to enable local authorities to better manage their waiting lists. The powers were also intended to target the ‘scarce resource’ of social homes at people who ‘genuinely need and deserve them’.

Between 2012 and 2017, council housing registers ‘lost’ 700,000 people. This may include some people without a need for social housing, but there is evidence the reform has led to homeless people and others in housing need being excluded.

This happens when local authorities apply categories of exclusion. These could be based on factors such as historic rent arrears, a history of anti-social behaviour or a previous offending history. It can also include restrictions on the grounds that an applicant has not lived for long enough in the area, or does not meet other local connection rules. Blanket exclusions applied in such an arbitrary way are out of step with the spirit and letter of The Homelessness Reduction Act (2017). This Act seeks every opportunity to prevent homelessness, regardless of people’s backgrounds.

Also the government’s Homelessness Code of Guidance states housing authorities should not use housing register qualification criteria to exclude homeless households entitled to reasonable preference in housing allocation.

While this includes households judged non-priority under the homelessness legislation, Crisis clients are sometimes told they are ineligible to register for housing. This is despite the government’s Homelessness Code of Guidance and local authority allocations policies stating that exclusions may be waived in specified or exceptional circumstances and individual circumstances taken in to account. Local authorities do not always have systems in place to ensure individual circumstances are in fact considered.

And where applications are turned down, homeless people may not be aware that they have grounds to seek review of a decision to exclude them from the housing register. They may also not have the capacity to manage an appeal. Participants in our national consultation to inform this plan highlighted problems with the use of housing register exclusions to restrict access to social housing, and called for an end to this practice.

The Ministry for Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) collects statistics on local authorities’ use of housing register exclusions on the grounds of local connection and rent arrears. Nine out of ten local authorities were found to use local connection exclusions, while just over half exclude people in rent arrears.197 Some councils also exclude households from registers if there are previous criminal convictions or previous unacceptable behaviour.

Our research found that such restrictions particularly affect homeless people. This can be because the circumstances that led to their homelessness may also be associated with rent arrears from a previous tenancy. It could also be because domestic abuse has contributed to tenancy loss and is identified by the social landlord as anti-social behaviour.

The Welsh and Westminster Governments should amend the Regulator of Social Housing (England) and Welsh Government’s regulatory objectives to include safeguarding and promoting the interests of homeless people as well as current and future tenants (mirroring the objectives of the Scottish Housing Regulator).

The social housing regulatory framework should ensure all social landlords assist households to meet their homelessness duties and deliver good outcomes for homeless people.

Impact

These changes are designed to improve consistency of practice across the sector and could be implemented in the short term. Timescales for changing regulatory objectives and guidance would require consultation and a short-medium term timeframe for implementation. Responsibility for change National governments and social housing regulators should provide strategic leadership to ensure social housing providers meet homeless people’s needs. Housing associations and local authorities and their membership bodies, and the relevant professional associations, must implement and share best practice.

Problem

The private rented sector is increasingly important in helping end homelessness. It is often the only viable housing option for single homeless people. Despite this, the ending of an Assured Shorthold Tenancy has become the leading cause of homelessness in England and Wales.

The sector is also characterised by a lack of security, poor conditions and high rents.

In Scotland, although poor conditions and high rents are a concern, the government has recently taken steps to improve security of tenure for private rented sector tenants. As already noted, local authorities often struggle to tackle poor conditions and standards in the sector. This is because of a lack of resources and basic data on private landlords and stock in their area. While the size of the private rented sector has grown, environmental health budgets have been in decline.

In England and Wales the private rented sector is characterised by short-term fixed contracts of only six or 12 months. These often fail to provide homeless people with the security they need to rebuild their lives. Beyond this initial fixed-term period, tenants can be evicted using a section 21 ‘no fault’ possession notice. They can be required to leave at relatively short notice (two months).

The loss of a private rented sector tenancy has become the leading cause of homelessness in England. The proportion of statutory homelessness acceptances by local authorities resulting from the termination of a private tenancy has increased significantly from 11 per cent in 2009/10 to 31 per cent in 2015/16204. Loss of rented housing accounted for the largest share (34%) of households considered by the local authority as threatened with homelessness in 2016/17.

Local authority tenancy relations services can help people sustain tenancies and mediate when disputes arise over poor management or conditions. However, the number of tenancy relations officers employed by local authorities has decreased in recent years.

The Scottish Government has implemented reforms designed to improve security and restrict the frequency of rent increases. The Private Housing (Tenancies) (Scotland) Act (2016) introduces a new private residential tenancy that must be used for every new private tenancy. The new tenancy type is open ended and the landlord will only be able to give notice under one of the 18 specified grounds for eviction.

If a tenant has lived in the property for more than six months they will be entitled to 84 days’ notice unless the landlord has served notice because the tenant is at fault. This gives private renting tenants in Scotland greater security of tenure than those in England and Wales.

The Welsh Government has legislated to simplify rental contracts, but the reforms do not significantly improve security of tenure for private renters in Wales. The Renting Homes (Wales) Act (2016) will replace the current secure and assured tenancy types in Wales with two new contracts.

These are a secure contract based on the current secure tenancy issued by local authorities and a standard contract. The latter is modelled on the current Assured Shorthold Tenancy used mainly in the private rented sector.

The reform aims to make it simpler and easier to rent a home. The standard contract will be initially granted for a fixed term and when the fixed term expires this will automatically convert to a periodic contract. The landlord will still be able to end the contract without cause after the initial six months.

In England, the Westminster Government is promoting tenancies of three or more years on new build rental homes. While longer-term tenancies are already more common in the build to rent sector,207 six or 12-month fixed term agreements remain the norm in the second hand rental market.

This is partly due to a lack of understanding from both tenants and landlords about how longer-term tenancies would work. Both parties may be concerned that a longer-term tenancy would limit their flexibility, for example to move or to sell the property if they needed to. Landlords also have concerns about their ability to evict tenants who build up significant rent arrears, cause extensive damage to the property or behave antisocially.

Unaffordable rent increases are also a concern for tenants as there is currently no limit to the amount that landlords can increase the rent by. This adds to the instability of private renting for tenants. A large rent increase can make the property unaffordable and force them to move, putting them at increased risk of homelessness

Elements of welfare reform, particularly the decoupling of Local Housing Allowance rates from market rents, have made the sector increasingly unaffordable. It has also left private renters vulnerable to rent arrears and subsequently eviction.

Unaffordable rent levels, up-front costs of deposits and rent in advance make it difficult for people on low incomes to find another property after receiving notice from their landlord. This puts them at greater risk of homelessness. Even where landlords let properties at rents within Local Housing Allowance rates, they are increasingly reluctant to let to people receiving Housing Benefit or to homeless people.

Participants during our national consultation strongly argued for reform of the private rented sector to address the issues highlighted here. This would help to ensure the sector is a secure and affordable housing option for homeless people or those at risk of homelessness. Participants with experience of homelessness emphasised the importance of improving security of tenure, and raised concerns about the affordability of deposits and rents.

"There is a lack of suitable and genuinely affordable housing – they are often poor quality and overcrowded with utterly high rents, which benefits don’t cover. The private rented sector is unstable, and [it is] far too easy to get evicted.” (Consultation participant, Croydon)

Interventions such as rent deposit guarantees, help to rent schemes and social lettings agencies help homeless people and other low income households access private rented tenancies. They do this in the following ways.

Projects build good relationships between landlords and their tenants, encouraging longer tenancies, and helping to prevent homelessness. Between 2010-2014, with funding from the then Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG), Crisis ran the Private Rented Sector Access Programme. It created more than 8,000 tenancies; 90 per cent lasted over six months. Evaluation on the programme showed that in three months, 92 projects saved more than £13 million in non-housing costs to the public purse.214 These projects also help tenants to gain employment, along with the support they receive to help make Universal Credit more sustainable. Crisis recently commissioned WPI Economics to identify the cost benefits to the government of both funding accredited help to rent projects and establishing and underwriting a national rent deposit guarantee. They identified that £31 million would be required per annum over a three-year period. This would be made up of:

The Westminster Government committed to providing £20 million to fund private rented sector access schemes in the 2017 autumn budget.

Social letting agencies are another way of providing a supply of decent private rented housing that can be targeted at homeless people. There are a range of models,215 but the key principle is that schemes operate as an intermediary between private landlords and tenants. They sometimes involve the agency leasing private properties and providing guaranteed rental income. The agency may provide management services directly or subcontract to a specialist/social housing provider. The agency ensures homes are of a decent standard, and the landlord receives a more secure income stream.

In some cases social lettings agencies may have a role in delivering or signposting to services such as employment support. Some social lettings agencies have become involved in property acquisition. This provides an asset base to further grow services, and there are examples of such provision targeted specifically at homeless people.

Homes for Good Community Investment Company

Homes for Good is an ethical property management company and lettings agent based in Glasgow. It lets homes to people on low incomes, and others disadvantaged in the housing market, including people receiving Housing Benefit. The agency manages properties for private landlords, and provides tenancy sustainment support to tenants, including budgeting advice, financial planning and employability assistance. A sister company, Homes for Good Investments buys and refurbishes derelict properties, which are then let through Homes for Good.

Fifty nine per cent of landlords with experience of letting to homeless people said they would only consider letting to homeless households if backed by such interventions.

If the private rented sector is to continue to provide a solution to homelessness, the problems described above must be addressed. National governments must build on recent reforms, and take the further steps recommended below to ensure homeless people can access stable, affordable and decent private rented homes. The changes recommended here would help to ensure the private rented sector provides a good solution for anyone who is homeless or at risk of homelessness.

Solutions

This would cover issues such as damp, mould and infestation, not covered by existing repairing obligations. Tenants would be able to take legal action against their landlord if they fail to comply with their obligations.

In England, the homes (fitness for human habitation and liability for housing standards) bill 2017-19, a private members bill currently before parliament, would achieve this if it becomes law.

The Renting Homes (Wales) Act (2016) introduces a similar requirement for rented homes to be fit for human habitation. This is expected to come into force in 2018.

In Scotland, properties are already required to be reasonably fit for occupation. If the landlord does not address an issue the tenant can take it to the First-tier Tribunal for Scotland (Housing and Property Chamber), who can make the landlord carry out the necessary work.

Full-scale reform of the legal aid system is outside the scope of this report. However, access to legal advice and support will be crucial to allow tenants to take action to remedy poor conditions if their rented home does not meet legislative standards.

Currently tenants can be deterred from taking legal action in disrepair cases because it can prove costly and little assistance is available for tenants who cannot afford to pay the legal fees.

Impact

We would expect to see standards in the private rented sector improving through the proposed legislation. It should make landlords more aware of their responsibilities and more inclined to act upon them due to the risk of having legal action taken against them. However, the impact may be limited if legal aid is not available for these cases.

As the bill is currently before parliament legislative change could be achieved quickly. It is likely to take longer for the full impact to be realised and that will be dependent on tenants’ ability to take legal action.

Responsibility for change

The Westminster Government.

An effective tenancy relations service would help to reduce demand on the legal system, by ensuring most cases are resolved outside the courts. A tenancy relations service would also play a key role in homelessness prevention. It would help to resolve issues that may otherwise escalate to the point where the tenant chooses to leave or the landlord serves notice.

Impact

This would allow renters to seek advice and take action both to remedy poor conditions and obtain compensation for any damages suffered. The impact could be measured by looking at the number of tenants bringing disrepair cases, and by measuring general improvements in conditions in the private rented sector, for example through the English Housing Survey or the Scottish Housing Quality Standard.

A fall in the overall number of statutory homelessness applications would be expected and specifically in the number of households becoming homeless as a result of a private sector tenancy ending. We would also expect more substantial changes, more quickly when tenants have access to legal aid to support their claims.

Responsibility for change

The Westminster, Welsh and Scottish Governments.

Introduce a national register of landlords for England, with all private landlords and letting agencies required to join.

To register, landlords must demonstrate that their properties meet basic safety requirements. They would also complete basic training on their rights and responsibilities as a landlord and pass a ‘fit and proper person’ check. Landlords failing to register would be subject to a fine. Those who repeatedly fail to meet their legal requirements should be removed from the register and prohibited from operating in the private rented sector.

The register would provide local authorities with basic information on the distribution of private rented housing stock in their area and private residential landlords operating locally. This would help them proactively manage the private rented sector in their areas. Local authorities could effectively target educational training and resources at amateur and accidental landlords, and effectively target enforcement work. Better data on the size and location of private rented homes would allow local authorities to make more informed and strategic decisions about the best way to tackle poor conditions. This includes whether or not to implement selective or additional licensing schemes.

Scotland and Wales both already have landlord registration schemes. Wales has one central register, Rent Smart Wales. The scheme launched in November 2015 and registration is required for all landlords.

Scotland has had landlord registration since April 2006. The scheme is managed by local authorities.

Information about registered landlords is now available on a searchable national database. A Shelter Scotland evaluation of the effectiveness of the scheme, three years after its launch, found it had helped local authorities provide advice, training and information for landlords.

The evaluation also found that complaints about bad practice had been addressed more effectively and voluntary accreditation schemes to highlight and reward good standards had been set up.

For England, a national, centrally managed register would limit the administrative burden for local authorities and landlords, allowing councils to focus on enforcing standards in the sector.

Shelter Scotland’s evaluation of the Scottish scheme found that some of the potential benefits were limited. This was because the scheme was administered on a local level by local authorities. They did not always have the resources to administer the register effectively, which led to an inconsistent application of the standards and use of sanctions to stop bad practice. The Scottish Government is currently consulting on improvements to the scheme.

Impact

Prospective tenants and private rented sector access schemes supporting homeless people could check if a landlord is registered. This would give confidence landlords understand their rights and responsibilities.

Success could be measured by the percentage of landlords registered, the amount of successful enforcement action taken by local authorities, and long-term improvements in the sector. This would include improved conditions and reduced instances of illegal evictions.

Responsibility for change

The Westminster Government.