The choices made by politicians can both cause and resolve homelessness. And since 1977 there have been targeted and successful political attempts to reduce it. When political action is backed across different parts of government it works well; it works best when policies that can also increase homelessness are stopped. This chapter sets out the political context for the plan, by giving details of the most successful post-war homelessness policies. It also summarises the policy choices that can hamper attempts to solve the problem.

Homelessness is a social and political phenomenon. It exists in its different forms and geographies in a variable state depending on how its causes are tackled and whether its solutions are adopted.

The portrayal of homelessness by experts in the field, and by the media, may emphasise the individual causal nature of personal stories. But there is a wider and more important truth to the phenomenon in Great Britain: homelessness can be both caused and solved by political action.

The levels of homelessness experienced in Great Britain today have been shaped by public policy choices including housing supply and affordability; welfare spending; eligibility for housing assistance. Intentionally or otherwise, these choices are also about whether to cause, to prevent, or to resolve homelessness.

This chapter details the major policy and political initiatives aimed at tackling homelessness, and their relative success. The longer-term structural drivers of the problem are also explored, to show relationships between homelessness and overall housing supply, employment rates, and the impact of economic cycles.

FOR GRAPHS SHOWING THE HISTORY OF HOMELESSNESS POLICY DECISIONS IN GREAT BRITAIN, PLEASE REFER TO THE FULL PLAN PDF.

NB: For technical notes on these graphs, please refer to the full plan PDF.

Until 1999, homelessness policy was directed from Westminster. Since then, homelessness policy has been directed within each nation.

After the Great Britain-wide Housing (Homeless Persons) Act (1977) came into force, the number of people receiving advice and assistance from their local authority (acceptances) increased.

This rise continued until 1989 and by the early 1990s homelessness had reached 146,290 acceptances.

Following the 1991 recession, acceptances in England started to fall in part due to a reduction in house prices. The Housing Act (1996) brought in new ways of recording total numbers of people coming forward for help (decisions) in England and Wales.

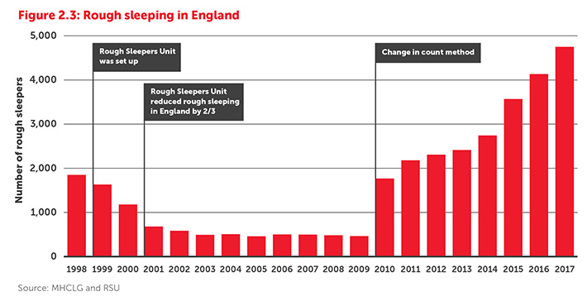

Rough sleeping had visibly risen in London and so in 1990, the Rough Sleepers Initiative was established. In 1999 the Rough Sleepers Unit was set up and achieved its target of a two third reduction in rough sleeping in England by 2001.

The Homelessness Act (2002) in England and Wales brought in new duties and preventative approaches including the introduction of Housing Options which meant more people could access advice and assistance. The increased use of prevention led homelessness acceptances figures to reach a low of 41,790 by 2009/10.

From 2010, rough sleeping and acceptances began to rise again with the impact of welfare reform, rising rents and the housing crisis. This led to the most significant change to homelessness legislation in 40 years, with the introduction of The Homelessness Reduction Act (2017) which brings about new duties to prevent and relieve homelessness.

Find out more about preventing homelessness.

Following the introduction of The Housing (Homeless Persons) Act (1977), the number of people seeking and receiving advice and assistance from their local authority rose. By 1980, the number was close to 10,000, by 1992 it had more than doubled, and by 2009 it had more than trebled.

The Housing (Scotland) Act (1987) put homelessness legislation within the remit of the Scottish Office. In 1997, the Scottish Rough Sleepers Initiative was introduced. The ‘Homelessness Taskforce’ followed in 1999. The recommendations of the taskforce started the development of a distinct Scottish approach.

It was not until The Housing Act (Scotland) (2001) that Scotland gained its first homelessness legislation. The Act introduced new duties that added to the existing legislation set out in The Housing (Homeless Persons) Act (1977).

The Homelessness Etc. (Scotland) Act (2003) completed the divergence from English legislation by aiming to abolishing priority need by 2012.

After reaching a peak of 32,294 in 2009/10 homelessness acceptances have gradually reduced and have since maintained a similar level.

Numbers of rough sleepers gradually reduced over time, until 2015 when numbers started to rise again. Acceptances are currently at 25,123 (in the last full statistical year).

After The Homeless Persons Act (1977) came into force, numbers of people accessing support, advice and assistance in Wales more than doubled between 1985 and 1993. It then fell to a low of 4,000 in 1999 before rising again to almost 10,000 in 2004.

The Homeless Persons (Priority Need) (Wales) Order (2001) was the Welsh Assembly’s first piece of homelessness legislation. It introduced new priority need categories to those set out by The Housing Act (1996). The new categories included 16 and 17 year olds and prisoners released as homeless.

The National Homelessness Strategy Wales 2003–2008 was launched by the Welsh Assembly and was the first national homelessness strategy in Great Britain. It aimed to set a national lead for tackling homelessness at a local level.

From 2005 there was a concerted focus and investment on the prevention of homelessness and the number of acceptances fell and remained at approximately 5,000 per year.

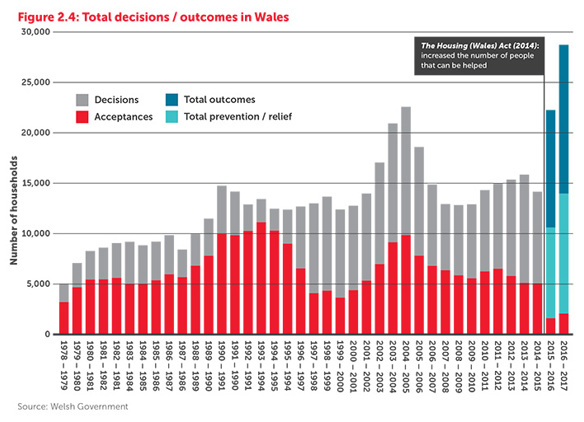

In 2014, The Housing (Wales) Act (2014) came into effect, giving local authorities new duties to prevent and relieve homelessness. This dramatically increased the number of people eligible for advice and assistance. Rough sleeping counts also started in 2015, indicating the rate of rough sleeping for the first time.

The history of the legislative response to homelessness dates back to the Poor Law attempts at reforming the character of destitute people, and The Vagrancy Act (1824). This Act still criminalises certain aspects of homelessness in England and Wales. It was not until the post-war consensus of universal welfare that national measures to alleviate extreme poverty, destitution and homelessness were attempted.

The post-war reforms to build universal entitlements to education and healthcare were accompanied by an attempt at housing protection for homeless households. The National Assistance Act (1948) formally abolished the Poor Laws, and gave new duties to the welfare departments of local authorities to protect ‘persons in need’.

The Act provided the first social safety net for citizens who did not pay national insurance, and was deemed necessary for homeless people, disabled people and other vulnerable groups. It states:

‘A local authority may, with the approval of the Secretary of State, and to such extent as he may direct, make arrangements for providing residential accommodation for persons aged eighteen or over who by reason of age, illness, disability or any other circumstances are in need of care and attention which is not otherwise available to them.’

The Act was an important forerunner to later and more comprehensive reform, especially in recognising the vulnerability and needs of families with dependent children. It did not, however, lead to the provision of suitable accommodation for homeless families or individuals. The severe housing shortage of post-war Britain was at its worst, and so in reality the local authority response was typically the provision of ‘reception centres’.

The 1977 Act provided an entitlement to long-term rehousing for people considered homeless in Great Britain (extending to Northern Ireland in 1988). The Act used a wide-ranging definition of homelessness, defined as having no accommodation in which it is ‘reasonable’ to expect a person to live. It also extended this to include those likely to become homeless within 28 days. Uniquely, it also gave homeless people the right to legal action in the courts to challenge decisions made by local authorities about their application for re-housing.

While this was a world first in legally sanctioned long-term rehousing provision for homeless people, the Act also distinguished between those who would qualify for assistance and those who would not. The scope of the Act meant that only households deemed to be in priority need were legally entitled to be rehoused.

Primarily this involved families with dependent children. Single people and childless couples had to prove they met strict vulnerability tests. In addition, homeless people had to prove they were blameless for their situation – that they were not intentionally homeless. Local authorities also only had to consider cases where applicants proved their local connection to the area. The full impact of this set of eligibility rules is explored in Chapter 13 ‘Homelessness legislation’, but the detrimental impact on ‘non-priority’ homeless people is well evidenced.

Notwithstanding the impact of this arbitrary distinction around who qualifies for assistance, The Housing (Homeless Persons) Act (1977) has had a dramatic positive impact for those it serves. Since the duties of the Act came into force, more than 4.5 million households have been assisted into alternative long-term housing, commonly referred to as being ‘accepted’ as statutory homeless.

The numbers of households accessing this entitlement have dramatically shifted over time. There are a number of factors that have influenced the fluctuations in ‘acceptances’ over the last 40 years. First, the late 1970s and 1980s saw the uptake of this new entitlement among eligible homeless households, coupled with a relatively healthy investment in social housing up until that point.

Second, a set of reforms in 2002/3 then had a dramatic impact in reducing acceptances over the subsequent seven years. The Homelessness Order (2002) expanded priority need criteria to include those deemed vulnerable as a result of leaving the armed forces or prison, or as result of fleeing violence. It also made 16 and 17 year olds a priority need group.

However, these reforms came alongside the formal introduction

of Homelessness Prevention (now known as Housing Options) via The Homelessness Act (2002). Services to prevent and relieve homelessness became a focus on local authority strategies (which were themselves made a statutory requirement). To back this new focus, the Supporting People programme allocated £1.8 billion of ring-fenced budgets to local areas.

These changes have affected the way in which the statutory homeless system has responded to demand. But the fact remains that the central principle of a right to re-housing has stood the test of time and political fluctuations.

In 1990, Housing Minister George Young established the first Rough Sleepers Initiative (RSI), which was a three-year programme for London. It involved £30 million of funding to increase outreach work, provide emergency hostel beds, and provide other forms of temporary and permanent accommodation for people sleeping rough.

This was extended for another three years in 1993, and an additional £60 million allocated. By this time political attention and competition on the issue had increased, with the Labour Party stating that homelessness was ‘the visible symbol of all that was wrong with our country’.

In 1996, as attention turned to a third phase of the RSI, ministers were faced with the need to extend the programme and funding outside London. However, the lack of data about the geography and scale of rough sleeping made it difficult to allocate budgets reliably.

From 1996, local authorities were asked to provide annual estimates to the government, and so the first ‘official’ estimates of the scale and distribution of rough sleeping were made. This was an important step forward, providing ministers with a greater chance of judging the progress of policies.

The change of government in 1997 saw a continuation of the work to tackle rough sleeping. The Major Government handed the lessons of the previous seven years to the Blair administration, with a new baseline of data and data collection from which to progress.

In 1998, the newly-formed government’s Social Exclusion Unit published a report into rough sleeping which, to some extent, broke from previous thinking on the issue. The report diagnosed causes to the problem that were wider than a lack of access to housing. This ‘social exclusion’ agenda sought to tackle structural factors including unemployment, low incomes and inter-generational poverty, and the individual impacts such as mental health, addiction and family breakdown.

With this approach came newly prescribed solutions. These included prevention measures for care and prison leavers, and a focus on multi-agency action at a local level, overseen by a national co-ordinating body. And so, in 1999, the Rough Sleepers Unit (RSU) was established and handed the target of reducing rough sleeping in England by two- thirds by 2002 (see figure 2.3). The then deputy director of Shelter, Louise Casey, was appointed to lead the Unit.

The RSU achieved its target a year early, applying a range of methods. These included expanding hostel provision and hiring new specialists in mental health and addiction services. Other methods involved establishing outreach teams to assess rough sleepers, and focussing on preventing those leaving the armed forces, the care system, and prison from sleeping rough.

The evidence for the success of different elements of this approach are assessed in Chapter 8 ‘Ending rough sleeping’. A crucial element was the political importance and authority ascribed to the target to reduce rough sleeping, and to the RSU itself. The RSU was given cross departmental authority in Whitehall and a reporting line to the Prime Minister.

It is self-evident in the dramatic rise in England of rough sleeping since 2008 that the absence of political targets, cross-government approaches, and sufficient budgets have all affected the increase in numbers.

The Scottish Rough Sleepers Initiative was established in 1997. In 1999 a target was set to make sure no one had to sleep rough in Scotland by 2003. Through the initiative, the numbers of people sleeping rough who presented to services fell by over a third between 2001 and 2003. While the target was not met, the initiative led to enhanced support in cities, while in some areas rough sleeping services were set up for the first time. The initiative also drove political and cultural changes within local authorities and led to a much stronger strategic focus on rough sleeping and homelessness at both local and national level.

In 1994, we published research showing that 25 per cent of single homeless people in England had served in the UK armed forces. Publication of this significant finding led, in part, to the formation of the Ex-Service Action Group (ESAG), to address the problem. ESAG themselves published research in 1997, which showed that London in 22 per cent of London’s homeless population were ex-service personnel. These studies revealed that the ex-services homeless population tends to be more disadvantaged than the wider homeless population. This is because they are older than average, more likely to have slept rough, and more likely to have physical health and alcohol problems. It is worth noting that counter to popular belief, this group did not experience significantly higher levels of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

This new body of evidence prompted successful cross-departmental political action. The Ministry of Defence (MoD) established the Joint Services Housing Advice Organisation, aimed at providing housing support for people before they left the armed forces. Tackling veteran homelessness became a priority of the Rough Sleepers Unit mentioned above. In 2002, the categories of homeless applicants with a priority need for rehousing were extended to include those deemed vulnerable because of having been a member of Her Majesty’s Forces.

By 2008, research in London showed a substantial drop in veteran homelessness, down to six per cent. This is attributed to significant efforts by the MoD to prevent homelessness, and concerted initiatives from ESAG to directly assist people, and indirectly lobby government for their interests.

In August 1999, two years after devolution of powers to Scotland, the Scottish Executive established a ‘Homelessness Taskforce’. The Taskforce was given a remit to ‘review the causes and nature of homelessness in Scotland’ and to ‘make recommendations on how homelessness in Scotland can be prevented and, where it does occur, be tackled effectively’. The group was made up of a range of sectors and experts, it met more than 30 times in three years, and presented a radical platform of reform in January 2001.

The most significant measure presented was the idea of extending the main homelessness duty to all eligible households by scrapping the concept of priority need. The Scottish Government accepted this recommendation and in 2003, The Homelessness Etc. (Scotland) Act (2003) was passed. The Act set a target date (the end of 2012) for the abolition of the priority need test in Scotland. After this date, local authorities in Scotland would be legally obliged to assist the rehousing of all eligible and non-intentionally homeless people.

A full exploration of the benefits of different legislative approaches is set out in Chapter 13 ‘Homelessness legislation’, but it is clear that this bold and progressive move has had a dramatic positive impact.

Scotland has effectively phased out the problem of ‘non-priority’ homelessness. With this expanded safety-net it has achieved a decline in homelessness that has bucked the trends elsewhere in the UK.

The abolition of priority need in Scotland should not be presented as a panacea. The recent rises in rough sleeping and of people living in temporary accommodation show how much is still to be done. However, The Homelessness Etc. (Scotland) Act (2003) was a political choice that demonstrated the power of positive social policy in tackling homelessness, and is a source of inspiration for international advocates in homelessness.

Following the advent of primary law making powers for the Welsh Government in 2011, the priority of tackling homelessness through improved legislation soon emerged. It was strongly backed by advocates in the third sector, but also by local authorities and academics. Dr Peter Mackie was commissioned by the Welsh Government to review homelessness legislation, and to make proposals for improvements.

The Mackie review sought to address two key weaknesses in the existing system. First, a growing inconsistency in preventative 'housing options' approaches, sitting outside the statutory framework, and second, often no 'meaningful assistance' was given to non-priority homeless people, especially single men. In response, Mackie proposed a ‘housing solutions’ model. This would switch the emphasis of local authorities to preventative and flexible interventions, aimed at resolving homelessness before the ‘main’ rehousing duty was necessary.

The proposed new approach would entail a duty on local authorities to 'take all reasonable steps to achieve a suitable housing solution for all households which are homeless or threatened with homelessness'. Mackie suggested extending the period when someone could be deemed to be threatened with homelessness from 28 to 56 days. He also suggested that the prevention duty should be owed to all applicants, regardless of priority need, local connection or intentionality.

These recommendations were adopted by the Welsh Government, but others were not. Most significantly, a recommendation to provide emergency accommodation to people who had 'nowhere safe to stay' was rejected. The Housing (Wales) Act (2014) was passed in 2014, with key homelessness duties coming into effect in 2015. The Act requires local authorities to carry out 'reasonable steps' to prevent and relieve homelessness for all eligible households.

These reforms have been largely welcomed in Wales, particularly because they have increased the number of people that can be helped, and have increased the flexibility of local authority services (see figure 2.4). The headline statistics report a 69 per cent reduction in homelessness acceptances between 2014/15 and 2015/16, and for people threatened with homelessness, 65 per cent had it successfully prevented in 2015/16.

As with legal reforms in Scotland, these positive results should be viewed within the context of on-going concerns and unresolved homelessness issues. It is also important to note that the reforms did not reduce the numbers of people needing help; rather it offered a broader and different set of ways to help. The Housing (Wales) Act (2014) also did little to tackle rising rough sleeping in Wales. There are concerns that a number of groups are still failing to access meaningful help, including those deemed to have 'failed to co- operate' with housing authorities.

Notwithstanding these concerns, the 2014 Act is another strong example of the power and positive impact that focused public policy interventions can have in preventing and tackling homelessness.

The two-tier homelessness system created by The Housing (Homeless Persons) Act (1977) has long been a source of concern for homelessness advocates. As detailed above, the introduction of the entitlements for re-housing has successfully helped end homelessness for more than 40 years. However, for many 'non-priority' and other ineligible households, that help is not available.

Evidence of the impact of this distinction is not hard to find. In its most acute form, rough-sleeping represents the failure of the homelessness safety net to catch people who need help, but so too does the many thousands of people living in hostels, night shelters, cars, etc. Following the introduction of legal reforms in Scotland (2003) and then Wales (2014), England has been the last country in Great Britain to consider legal reforms to widen the statutory homelessness safety net. In 2014 we published our Turned Away report. This documented the experiences of 'mystery shoppers' who presented cases of single homelessness and significant vulnerabilities in 87 local authority visits across England.

The report painted a picture of systematic 'gatekeeping' whereby people were denied the chance to explain their needs and access services. It also revealed how poorly homeless people can be treated by local authority housing professionals.

In 2015, we assembled a panel of experts to consider options for legal reform in England. This group was drawn from leading homelessness charities, academia, local authorities, housing specialists and leading legal experts. It was chaired by Professor Suzanne Fitzpatrick from Heriot-Watt University. Over six months, the group considered recommendations for reform that would increase entitlements for single homeless people, and also protect the duties owed to priority households (typically families with dependent children).

In February 2016, the panel produced a set of proposals that owed much to the emerging example in Wales. The proposals focused heavily on the benefits of both homelessness prevention, and of removing eligibility barriers for homeless households when accessing prevention and relief assistance. These proposals were crafted into a potential Bill to demonstrate to parliamentarians the necessary legal steps for achieving the aims of the panel report.

Later in 2016, Conservative back-bench MP Bob Blackman was drawn in the private members' ballot for the parliamentary session, and chose to adopt the reforms set out by the panel. Mr Blackman’s proposals became the Homelessness Reduction Bill, for which he gained cross-party and government support. The bill received royal assent in April 2017.

The duties contained in The Homelessness Reduction Act (2017) came into force in April 2018, and so the impact of the new duties to prevent and relieve homelessness are as yet unknown. As with the recent changes in Wales, the final legislation did not contain suggested duties to give emergency accommodation to those in immediate danger of rough sleeping. Nonetheless the Act is a radical reform made possible by a renewed political appetite to tackle homelessness.

The homelessness policies and initiatives listed in this chapter represent the largest and most successful targeted domestic public policy on homelessness to date. They show what can be achieved when politicians make bold decisions and seize the agenda. However, it is worth noting the influence of non-homelessness policy in driving trends over time. Wider policy in housing and welfare may not be driven by imperatives to tackle homelessness, but they do have a direct impact on the problem, and indirectly affect the efficacy of homelessness policy and practice.

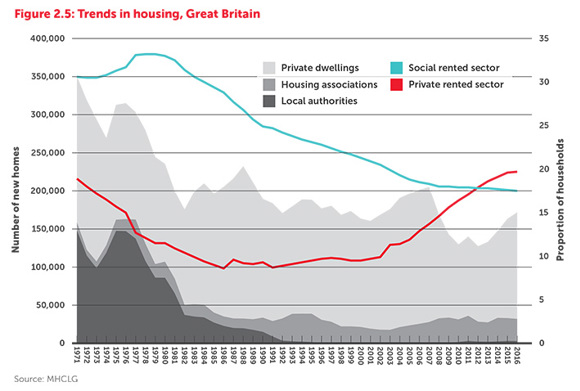

Figure 2.5 illustrates the decline in house building and availability of social rented accommodation over the last 45 years. In 1970, there were 157,026 local authority housing completions across the UK. By 2004 this had dropped to just 140, and the latest data for 2016 showed 3,305 completions. The lack of affordable housing to tackle homelessness, including the reduction in available stock through right to buy, are explored fully in Chapter 11 'Housing solutions to homelessness'. However, it is clear that the chronic lack of accessible and affordable supply is a key determinant in whether local authorities across Britain can discharge their homelessness duties. This is regardless of how progressive the homelessness policies are.

While overall supply of affordable accommodation directly affects homelessness trends, local authorities consistently cite changes in welfare policy (and particularly Housing Benefit reductions) as posing the greatest challenge in assisting homeless people. While the three nations of Great Britain have different statutory frameworks for tackling homelessness, and varying housing pressures, the limitations posed by welfare policy are felt strongly in all countries.

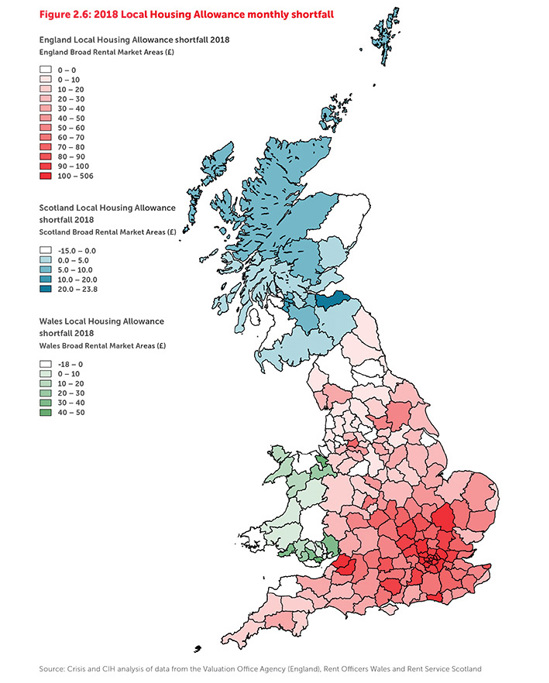

Chapter 10 ‘Making welfare work’ contains a full exploration of welfare policies impacting homelessness. But figure 2.6 demonstrates clearly the current gap between private rental prices and the Local Housing Allowance rates available in those areas. As with the lack of affordable housing supply, this is a policy choice made by successive governments that both causes homelessness and restricts the ability of local authorities to address it. The failure to address causal elements of homelessness in welfare policy can also call into question the very logic and value for money of government strategies seemingly at odds with each other.

There is a strong link between people experiencing poverty and an increased risk of homelessness. Further recent evidence has highlighted the link between the risk of homelessness and experience of childhood poverty. Logically those with the lowest levels of income are at greatest risk of not being able to afford housing costs.

However, it is not inevitable that economic recession and high unemployment will lead to homelessness in greater numbers than at points of relative prosperity in economic cycles. This is partly because recession can lead to greater affordability of housing costs, driven largely by increased affordability of mortgage payments. It is also because policy makers can decide whether (or not) to provide a social security safety net that offers sufficient protection from homelessness when required.

Unemployment rates do not necessarily correlate with trends in homelessness acceptances. Indeed there have been points in the late 1980s and early 2000s when the opposite occurred. This can be explained in part by the time-lag effect of unemployment leading to homelessness.But it must also be attributed to the effectiveness of protections in social security, including homeless prevention and rehousing. The key test for policy makers is whether and how they are prepared to complete this safety net to fully protect those at risk during economic downturns and recessions.

Public policy initiatives to tackle and reduce homelessness are proven to make a lasting and positive impact. The reforms outlined in this chapter show that homelessness is a phenomenon that can be predicted and prevented. For those who do lose their home, it is a problem that can be solved quickly and permanently.

The Housing (Homeless Persons) Act (1977) provided the basic entitlements to homelessness support from which both extended rights and targeted interventions have successfully grown.

However, decades of under-investment in affordable housing and recent erosion of welfare entitlements have seriously undermined the impact of homelessness protections and local governments' ability to deliver them.

The question for governments across Great Britain must now be whether they are prepared to complete the job of policy making to end homelessness. Homelessness policy is now devolved, but in all three nations there still exist populations for whom the statutory safety net is insufficient.

Will the current renewed policy attempts in Scotland and England, or future attempts in all three nations, address these gaps for ineligible and ill-served groups such as rough sleepers, or migrant homeless people? And crucially, will the wider structural causes of homelessness in housing supply for each government, and welfare reform for the Westminster Government, be woven into future policy?

Further chapters in this report lay out the necessary policy changes to achieve an end to homelessness over time across Great Britain.