Great Britain has some of the most effective and forward-thinking homelessness legislation in the world. It protects hundreds of thousands of people annually. But despite this success, there are still winners and losers from the statutory systems in England, Scotland and Wales. The time is right to complete a strong safety net of legal protection for all homeless people.

In this chapter we propose the ‘ideal’ statutory homelessness systems for England, Scotland and Wales. Our proposals draw on learning and evidence from across Great Britain and internationally. We present the rationale for a strong and complete safety net of legal protections and entitlements for homeless people.

To gather an assessment of the ideal legal framework, we commissioned an analysis and proposal for wholesale reform from the two leading experts in academia and housing law. They are Professor Suzanne Fitzpatrick from Heriot-Watt University, and barrister Liz Davies from Garden Court Chambers. Their full proposal and paper will be published separately. It provides additional context and arguments to that contained in this chapter. Unless otherwise stated, all analysis and references in this chapter relate to the Davies and Fitzpatrick paper. The table of summary recommendations for national governments at the end of this chapter reflect agreed principles, but are entirely written by Crisis.

Before considering the ideal statutory homelessness system we should ask, why have statutory homelessness rights at all? No other country in the world has anything equivalent and some other countries, especially in Europe, seem to have low levels of homelessness. There is a right to emergency shelter in narrowly defined circumstances in a few European states, including Germany and Sweden, and in a single jurisdiction in the US (New York City). However, enforceable rights to permanent or settled housing for homeless people are limited to the UK.

In some countries, including Ireland, enforceable rights for homeless people have been explicitly rejected as ‘adversarial’. They have been seen as counter-productive in the difficult task of rationing scarce housing resources.

Some people argue that enforceable legal rights can contribute to social policy becoming over legalised, frustrating its fundamental purpose and encouraging a defensive, process orientated mindset in housing practitioners. They argue that this mindset can then result in practitioners becoming more concerned about protecting themselves from legal challenge than addressing the needs of homeless people and other service users. Others argue that enforceable legal rights direct power and resources into the hands of the legal profession and away from service provision.

Against this, international comparative research suggests that some enforceable statutory rights have formidable advantages. This includes countering the tendency for social landlords to exclude low-income and vulnerable households from their properties when such rights are absent. Such rights can create a better balance of power, giving homeless people an enforceable right of action against those charged with assisting them, should they fail in their responsibilities. Receiving assistance as a matter of right, rather than as a matter of discretion, may help to safeguard the self-respect of those who may otherwise be made to feel (deliberately or otherwise) like humiliated supplicants.

Ken Loach’s 1966 film Cathy Come Home shockingly portrayed what happens when homeless people are not entitled to statutory rights and are dependent on discretionary powers exercised by local authorities. It showed a system infused by decision making based on moralising value judgments. The system broke up the whole family – initially separating Cathy and her children from her husband Reg – and finally the children from Cathy as they were taken into care.

The film helped to foster the environment that led eventually to the passage of The Housing (Homeless Persons) Act (1977). This Act set up the statutory duties on local housing authorities to provide accommodation and assistance to homeless people. We focus on these duties in the remainder of this chapter.

The Housing (Homeless Persons) Act (1977) was a major step forward in legally protecting homeless people. It set out how local authorities must make accommodation available to certain categories of homeless people; mainly families with children and vulnerable adults. The long-term accommodation provided under this legislation was usually council housing.

The legislation also strongly reinforced an ongoing shift from council house allocations based on desert (judged by various moral criteria) to ones based more clearly on housing need.

The 1977 Act covered all of Great Britain, and was extended to Northern Ireland in 1988. This Act was consolidated into separate legislation in England and Wales on the one hand, and Scotland on the other. The basic statutory homelessness framework remained very similar throughout the UK until the 1990s. But there is now a significant differentiation in homelessness law in each jurisdiction, as is discussed in the next section.

Strictly speaking, the 1977 Act did not create rights – rather it imposed duties on local housing authorities once certain conditions were triggered. However, critically these duties were precise enough to allow legal recourse to people whom local authorities fail in their duty. Any failure to comply with the duty could be enforced by the applicant through the courts. Individually enforceable rights are far more practically useful than constitutional or other abstract rights to housing which are common in continental Europe and elsewhere.

As described above, the 1977 Act is internationally unique, and some of its features are particularly important. First, the definition of homelessness it employed was exceptionally wide. You are deemed legally homeless if you have no accommodation in which it is ‘reasonable’ to expect you to live together with your family. In many other countries, notably the US, a much more literal definition of homelessness is used – focused only on those sleeping on the streets or in night shelters.

Second, local authority obligations are not limited to those ‘homeless today’ but also include people likely to become homeless in the near future. Historically this is 28 days, although it has now been extended to 56 days in more recent legislation. Consequently, many of those accepted by local authorities under the homelessness legislation have never actually been without any form of accommodation. Only a very small minority have slept rough.

However, there were also significant limitations to the scope of the 1977 Act. Most importantly, only those homeless households in priority need were legally entitled to rehousing. This meant mainly families with children, with single people included only where they met vulnerability tests, which could be tightly applied.

Other limitations included the requirement that even these priority need groups be blameless for their predicament. Those found intentionally homeless were entitled to temporary rather than settled accommodation. Local authorities could transfer the rehousing duty to other local authorities on local connection grounds. People ineligible for assistance due to their immigration status were also not entitled to any help under the homelessness legislation anywhere in Great Britain, even if they have a priority need. There have been some changes to this in recent years for migrant homeless people from Europe.

Once the local authority has determined whether it owes a duty to secure accommodation, how it performs that duty is largely a matter for them. This is provided that (as a bottom line) the accommodation secured is suitable for the applicant. Case law has established that the accommodation must be suitable for the specific needs of that individual applicant, and of his or her household. Accommodation must also be affordable for an applicant, and the location, physical features, and other elements of the accommodation are also relevant.

If at the end of this process an applicant is not accommodated under homelessness duties, and has children, or a need for care, and cannot find their own accommodation, they can ask children’s or adult social services to assess the needs of the children or of the person needing care. This includes any need for accommodation, and to provide services to meet any assessed need.

Those assessments can contain value judgments about an adult’s past behaviour, reasons for homelessness etc. It is rare, but not necessarily unlawful, for children’s services to conclude that accommodation will be offered to a child and not to their parent(s), splitting families apart in the process.

This system, whereby social services assess needs and decide how to provide any services, is the modern equivalent of the help that Cathy (in Cathy Come Home) received from social services in 1966. This help involved discretionary judgments, rather than enforceable duties.

There are many further questions that arise during the process of an application for homelessness assistance. It is for a local housing authority to determine factual questions (eg ‘are you homeless?’), but it is also for a local authority to make a judgment of certain conditions. One key judgment is whether or not someone is ‘vulnerable’.

In England and Wales, this is a crucial test determining whether a person is in priority need and thereby owed the main rehousing duty.

These evaluative or discretionary judgments can result in conclusions that an applicant regards as wrong, or have harsh consequences for them. This could be when someone is not considered vulnerable, or when an applicant is offered accommodation in another town or city and told that location is considered suitable for them.

When these judgements are contested by the applicant, the opportunity for an internal review of those decisions, as is provided in all three nations, is helpful. It provides a second eye and an opportunity to make representations, and the review is not limited to issues of law. A reviewing officer at a local authority can come to a different decision to the first decision-maker on the same set of facts.

However, the reviews process is not independent. It is undertaken either by a senior employee of the same local authority or by a contractor to the authority. The only redress for an applicant from an adverse review decision is to appeal to the County Court on a point of law in England and Wales.

In both jurisdictions and in Scotland, there is also the possibility of seeking a judicial review of the lawfulness of local authorities’ decision-making. This may then be overturned on grounds such as ‘manifest unreasonableness’ or taking into account ‘irrelevant factors’. These are useful tools in administrative law, in that it regulates good decision making. However, they do not provide immediate redress for a dissatisfied applicant.

A further weakness of The Housing (Homeless Persons) Act (1977) is that it is only focused on resolving housing needs, and not any wider support needs that homeless households may have. The Act is very much crisis focused. It targets situations where homelessness has already occurred or is imminent – rather than facilitating more upstream forms of prevention with groups known to be at high risk. This is linked to the fact that, while there were very general duties across Great Britain for other public bodies and social landlords to provide ‘reasonable assistance’ to local authorities in the discharge of their homelessness duties, these were so vague as to be unenforceable.

Difficulties faced by local housing authorities in securing necessary assistance from social services, health and criminal justice services in delivering their homelessness duties is a recurring theme across Great Britain. Likewise, there have been longstanding tensions over nominations of homeless and other prospective tenants by local authorities to housing associations. These occur where the prospective tenant has qualified under the local authority’s allocation scheme, but is ineligible under the housing association’s scheme.

All three British jurisdictions have developed their homelessness systems in different ways since the 1990s, and each has strengths and weaknesses. None are ideal, but there are lessons to be drawn from each in determining the ideal statutory system.

Chapter 2, ‘Public policy and homelessness’, details the political process and rationale for the major legal changes in England, Scotland and Wales. The detail and consequences of those changes are summarised below.

Scotland

The first specifically Scottish piece of legislation governing homelessness was The Housing (Scotland) Act (1987), Part 2. This remains in force and contains the legal framework for homelessness duties and powers on Scottish local authorities. However, Scotland’s legal and policy framework radically diverged from the rest of the UK early in the post-devolution period. This process began with The Housing (Scotland) Act (2001), which introduced new duties on local authorities to provide temporary accommodation for non-priority homeless households.

This was a crucial step because it established the principle that nonpriority households should be entitled to material assistance from local authorities. The Housing (Scotland) Act (2001) also imposed obligations on housing associations to give ‘reasonable preference’ to all homeless households in their allocations policies.

More radical reforms were introduced in The Homelessness Etc. (Scotland) Act (2003) with the gradual expansion and eventual abolition of priority need by the end of December 2012. This Act also allowed for the softening of the intentionality test. This gave local authorities discretion to investigate whether a household had brought about their own homelessness. It also ensured that some form of accommodation and housing support was available to those found to be intentionally homeless. The Housing (Scotland) Act (2001) also gave the Scottish Government the power to suspend the operation of local connection rules. To date neither of these amendments has been brought into force.

A duty to assess the housing support needs of homeless households, and to ensure that housing support needs are met, was introduced by The Housing (Scotland) Act (2010). The relevant provisions began in June 2013.

The clear strength of the Scottish system is that there is an (almost) universal statutory safety net. This removes the traditional discrimination against single people within the statutory homelessness system. This has undoubtedly led to much better treatment of this group by local authority homelessness services. It is also likely to be related to overall reductions in rough sleeping since The Homelessness Etc. (Scotland) Act (2003) came into force. However, across the country growing demand for homelessness assistance, coupled with a reduction in the available social housing, has presented challenges in delivering this universal rights model. The number of households living in temporary accommodation almost trebled in Scotland between 2001 and 2011 and, after a small decline, is now close to record levels.

From 2010 onwards, the Scottish Government promoted prevention measures along the lines of the English Housing Options approach. A sharp drop in homelessness applications and acceptances followed, and as in England, this prompted concerns about applicants being diverted from or denied assistance (often referred to as gatekeeping) in certain local authority areas.

In 2014, the Scottish Housing Regulator published a thematic inquiry, which endorsed the principles of Housing Options, but also echoed concerns, expressed by other commentators, about the diversion of people from statutory homelessness.

Wales

Following the devolution of the right to pass primary legislation in the areas of housing and homelessness, a radically new approach was contained in The Housing (Wales) Act (2014). This Act came into force in April 2015. It strongly emphasised earlier intervention and assistance tailored towards the specific needs of households threatened with homelessness within 56 days. This preventative assistance is available to all eligible households who are homeless or threatened with homelessness, regardless of whether or not they have a priority need.

The aim is to help people remain in their own homes (by trying to solve the problem that resulted in the threat of them having to leave) or to find alternative accommodation quickly. This is so that they do not experience the crisis of actual homelessness.

For those who are already homeless when they approach the local authority, or whose homelessness cannot be prevented, local authorities have to take reasonable steps to relieve their homelessness. The interventions that local authorities ought to have available are set out in an accompanying code of guidance.

The priority need test remains relevant in three aspects

Nearly three years after implementation of this new approach, there is consensus among commentators and housing practitioners that The Housing (Wales) Act (2014) has had highly beneficial impacts. Service users have also given generally positive feedback. It has begun the process of re-orientating the culture of local authorities towards a more preventative, person-centred and outcome-focussed approach.

The Housing (Wales) Act (2014) has brought about a much better service response to single homeless people in particular. Although variations in service outcomes remain across Wales, and successful outcomes for single people still tend to be poorer than for families with children. In 2016/17, two thirds (62%) of ‘prevention’ and 41 per cent of relief interventions were successful. There has been a subsequent massive reduction in the number of households owed the final duty to secure accommodation.

The success of the prevention and relief models means that the becoming homeless intentionally test has become of far less significance than was previously the case. This is because it is only applied to an applicant who has a priority need, and where relief efforts to help them find their own accommodation have been unsuccessful.

Until 2019, local authorities can choose whether to apply the intentionality test, and, if so, to apply it to all priority need groups or only to some of those groups.

However, even under this more inclusive statutory model in Wales, there is a substantial group of homeless people for whom the system will not resolve their homelessness. This group includes:

Proposals for a (priority need blind) duty to provide somewhere safe to stay for all applicants, particularly those at risk of sleeping rough, were abandoned during the passage of the 2014 reforms. This followed opposition from the Welsh Local Government Association (WLGA).

In April 2018, the Equalities, Local Government and Communities Committee of the National Assembly of Wales recommended abolition of the priority need test.

England

The approach applied in Wales since April 2015 was broadly introduced in England on 3 April 2018, when amendments inserted into The Housing Act (1996) by The Homelessness Reduction Act (2017) came into force.

The amendments inserted by The Homelessness Reduction Act (2017) mirror the Welsh approach in the following ways.

There is also a duty to carry out an assessment of the applicant’s case and, following that assessment, to draw up a personalised housing plan that should be agreed with the applicant. That plan contains the steps that the local housing authority will take to help the applicant keep, or find, accommodation. It also includes the steps the applicant agrees to take, or is told by the local housing authority would be reasonable for him or her to take.

The consequences of a ‘deliberate and unreasonable refusal to cooperate’ decision are less harsh for applicants in England who have a priority need and have not become homeless intentionally than they are for applicants in Wales.65 In England, a local housing authority continues to be under a duty to accommodate those applicants, although that accommodation duty can be ended by the offer of a suitable six-month Assured Shorthold Tenancy.

In both England and Wales, the intention behind these new statutory duties is that the help provided will not be routine, standard advice, putting the onus to find accommodation on the applicant. Instead it will be part of a new atmosphere, where local housing authorities understand the homeless applicant’s situation and make every effort to help him or her find accommodation.

As in Wales, there remain no enforceable legal duties to accommodate those who are sleeping rough. This makes the English and Welsh legal safety net weaker in this specific respect than several other European countries.

Unlike Scotland, but similar to the current position in Wales, the priority need test remains in force. This means, as has been the case since 1977, the only applicants guaranteed accommodation are those assessed as having a priority need and not intentionally homeless.

While, unlike in Wales, there are no plans to limit the scope of the intentionality test in the case of families with children, the test becomes of less relevance. This is because it does not apply at the prevention or relief stage. However, when it comes to the final duty to secure accommodation for priority need applicants, the test remains.

It remains to be seen what affect the power for local housing authorities to discharge their prevention and relief duties on the grounds that someone has ‘deliberately and unreasonably refused to cooperate’ will have. The intention is that such a decision would be a last resort. An applicant must first receive a written warning and be given an opportunity to comply. And the wording of the statute, with the Code of Guidance, makes clear that the bar is set high; higher than in Wales. An applicant must be acting deliberately, not foolishly.

Examples given in the Code of Guidance are where an applicant persistently failed to attend property viewings or appointments without good reason. And as noted, unlike in Wales, even applicants who have deliberately and unreasonably refused to cooperate will be entitled to accommodation. This is providing they have a priority need and have not become homeless intentionally. Although the minimum tenancy length for discharge of duty will be six not 12 months as it is in the main discharge of duty.

The vigorous adoption of Housing Options from 2003 onwards can be considered both a strength and a weakness of the English model to date. The strength lies in the proactive, problem-solving approach. The weakness is the risk of unlawful gate keeping. A key contribution of recent reforms in England and Wales is to bring these formerly non statutory activities into the heart of the legislative framework. This means that Housing Options activities can be better regulated, and also encouraged, as local authorities engaging in good preventative work will no longer be exposed to legal challenge.

One particular aspect of gate keeping addressed by The Homelessness Reduction Act (2017) is the widespread failure to take applications for homelessness assistance from private tenants who have been served with a section 21 notice.73 This notice gives them two months to leave the property. This practice should now change, as the Act is clear that someone who has been served with a valid section 21 eviction notice is threatened with homelessness. Consequently the duties to carry out an assessment of his or her case, draw up a personalised plan and engage in prevention activities will apply.

Using the learning from all three statutory homelessness systems in Great Britain, and that gained from international comparisons, Davies and Fitzpatrick have laid out the key principles of an ideal statutory homelessness system.

This is to ensure all reasonable steps to avert or resolve the relevant housing crisis are taken before homelessness occurs. These prevention duties should apply to all household types. Secondary legislation should define the minimum list of interventions that local authorities ought to have available in relevant cases. This list should be updated periodically as new interventions are shown to be effective. At this stage of the process in particular, there should be an attempt to minimise the use of the potentially stigmatising term ‘homeless’ altogether. The emphasis should instead be on addressing housing need, options or solutions.

These local authority duties should be part of a wider systemic approach where upstream forms of prevention are targeted at groups that we know to be at high risk of homelessness. This also requires a duty to prevent homelessness being placed upon key public agencies outside local authorities, such as the prison service (see Principle 6(b)).

The immediate safety net is access to emergency accommodation, which must be suitable. This will require resources to be allocated by governments.

Crucially, however, the form of settled accommodation used to discharge the main statutory duty to relieve homelessness should be broadly drawn. It should be suitable which includes affordable. This means that rental costs do not need topping up from subsistence benefits and that the accommodation can reasonably be argued to be offered on terms equivalent to those enjoyed by other people in the broader population. For example, when homeless people are offered social housing, they should be given the same number of suitable offers as other housing applicants.

For those made offers in the private rented sector, the minimum tenancy length should match that which is standard across the sector. We would like to see the length increased substantially from the current norm of six or 12 months in English and Welsh Assured Shorthold Tenancies (see Chapter 11, ‘Housing solutions’)

Scope should also be allowed for discharge of duty into innovative forms of accommodation. This could include: Housing First programmes, where participants should have social or private sector mainstream accommodation, supported lodgings, and other forms of longer-term ‘community hosting’ in appropriate cases.

This breadth of rehousing options helps to promote a problem-solving ethos. It is also pragmatic. Even in the ideal homelessness system, it will never be possible to deliver the perfect housing outcome desired by every applicant, and expectations must be managed. It also reinforces the homelessness system’s role as an emergency safety net which reinserts people back into the housing market and ordinary accommodation settings as rapidly as possible.

Principle 3(a): This broadening of the range of discharge options open to local authorities will weaken, but not sever the link between homelessness duties and social housing allocations. Statutory homeless people should continue to receive reasonable preference in local authority housing allocations, and housing associations in England and Wales should give homeless households ‘reasonable preference’ in their allocation policies, as is already the case in Scotland. A review of the operation of nominations agreements in all three countries in Great Britain would be beneficial. These are a constant source of complaint from both local authorities and housing associations, but only limited evidence is available on current practice at local level.

The current intentionality test goes far beyond what is required to control what might be considered to be any perverse incentives to access homelessness assistance. There is a strong case for moving away from this test, and instating another. It should be more tightly defined and have strictly limited consequences.

A new test would involve focusing on deliberate manipulation of the homelessness system. For example, this could involve collusion between an applicant and parent or householder who has excluded them. It would ideally require local authorities to demonstrate that the applicant had actually foreseen that their actions would lead to their becoming homeless. At present, all that must be shown is that the act that led to the loss of accommodation was deliberate, not that the link between this act and homelessness was foreseen or even foreseeable by the applicant.

The proposed consequence of this deliberate manipulation test would be restricted. Under this proposed scheme, households found to deliberately manipulate would receive no additional preference in social housing allocations because of their statutory homeless status. This test would have no bearing on any other homelessness-related entitlements.

In proposing this, Fitzpatrick and Davies accept the need to fairly distribute the burden of tackling homelessness between local authorities. However, they propose better ways to manage this necessity than the current crude local connection rules. Although the current rules are intended simply to determine which local authorities have a duty to provide settled housing, they are often used (unlawfully) as a gate keeping filter. Four potential ways forward are suggested, none of which are mutually exclusive.

However, children at risk of homelessness must be protected from the consequences of their parents’ decisions, however ill judged, for at least two reasons. First, children’s vulnerability and inability to fend for themselves in the housing market provides robust justification for ongoing state intervention and protection. Second, there can be no legitimate moral basis to hold children responsible for decisions over which they have no control. The Children Act (1989), The Social Services and Well-being (Wales) Act (2014) and The Children and Young People (Scotland) Act (2014) should be amended to make it clear that, in these circumstances, children’s services will keep the family together. Amendments should also make it clear that where the children are at risk of homelessness, accommodation will be provided for the whole family.

Similarly, for vulnerable single homeless people, strengthening of the duties of adult social care services will be key. There should also be appropriate opportunity to make a fresh application for homelessness assistance.

All relevant forms of support should form part of the personalised plans required by the recent legislation in England and guidance in Wales. These plans should extend beyond housing support, to health, social care and other relevant support, bearing in mind that not all homeless households will have additional support needs.

Scotland already has an explicit housing support duty in place, while in Wales and England the relevant duty is limited to making an assessment of support needs. A statutory duty to meet housing support needs would be especially beneficial in England, where the provision of housing support services has been cut by around two-thirds since 2010.

Cooperation duties in Wales were somewhat strengthened by The Housing (Wales) Act (2014) in relation to social landlords and children’s and adult’s services. While in England, The Homelessness Reduction Act (2017) has imposed on some public authorities a new duty to refer those at risk of homelessness to local housing authorities. However, stronger statutory duties to both prevent and alleviate homelessness on the part of other public bodies are likely to be more effective. This is especially true if embedded in the core legislative frameworks that structure how these bodies operate rather than isolated within homelessness legislation.

A duty to prevent homelessness placed upon key public agencies outside local authorities will support the prevention duties on local authorities discussed in principle 1. Key here would be both duties to prevent and cooperate integrated into social services/social work services, health, and criminal justice legislative frameworks.

The Scottish Housing Regulator has played a key (but reducing) role in the monitoring and inspection of homelessness services in Scotland. This could be looked to as a starting point in building a model for England and Wales.

A regulator, with a rolling programme of inspection and thematic reports, would be even more crucial in England. This is because there are a large number of local authorities and it is difficult for the government to keep a grip on what is happening across the country. This regulatory role becomes more important in direct proportion to the amount of flexibility that authorities are allowed in discharge of their statutory duties. It should also regulate housing associations to ensure effective cooperation with local housing authorities in the discharge of statutory homelessness functions.

If the principles above are adopted there would be fewer challenges to local authority decisions. This is because everyone would be entitled to some form of accommodation. Furthermore, the issues of whether an applicant is vulnerable and/or has become homeless intentionally would have fewer significant consequences. The disputes that might arise could then be over the suitability of the accommodation offered. Where disputes occur, the following are required.

Principle 9: Much more emphasis should be placed on training and supporting frontline homelessness officers. They work in a quasi-judicial capacity, yet there is no specified standard of educational attainment or prescribed professional qualification for their roles. Under Housing Options, and certainly under the ideal homelessness system, they would be expected to develop new problem-solving, person-centred and creative approaches. These approaches require different skills to those used in statutory assessments.

An ongoing emphasis on professional training and skills development among frontline homelessness workers is essential to the successful implementation of progressive legislation.

Principle 10: Changes in immigration legislation, with impacts upon housing, social welfare and employment, have created a ‘hostile environment’ for certain groups of migrants to the UK. These changes have been associated in recent reports with an increase in destitution among refused asylum seekers in particular. Various groups of migrants to the UK have differing legal statuses, and not all will be able to enjoy the same access to homelessness entitlements as UK citizens. However, it is unacceptable in a wealthy country to have people sleeping and starving on our streets. Davies and Fitzpatrick suggest that at the very least minimum subsistence benefits and basic accommodation must be made available to all regardless of immigration status. Chapter 12, ‘Ending migrant homelessness’, suggests further reforms to open up access to the statutory system, alongside other reforms for different groups of migrant homeless people.

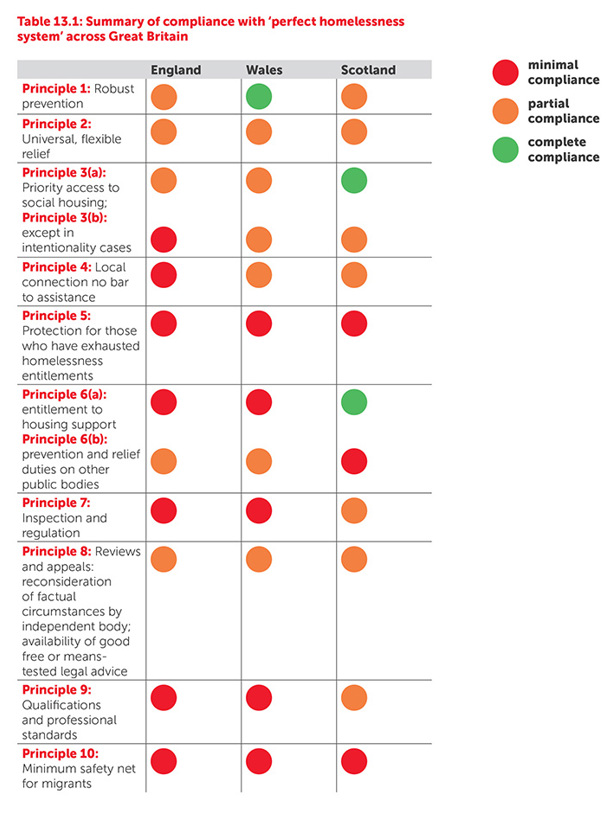

Having established the principles that should be applied in the ideal homelessness system, the section below looks at what is needed to achieve this in each country. Table 13.1 summarises the extent to which the principles above are already met in the three countries of Great Britain.

This section does not prescribe a legislative vehicle or remedy in each case. It is assumed, however, that in each context there is a need for a comprehensive parliamentary/ assembly process to establish these provisions.

England and Wales have gone furthest in implementing a robust preventative model. Scotland has some catching up to do in this respect, notwithstanding the rolling out of Housing Options since 2010 (Principle 1). There is no equivalent in Scotland of the flexible form of homelessness relief now provided for in the English and Welsh legislation. But, the universal dimension of Principle 2 is achieved via the abolition of priority need in Scotland. In England and Wales there is no guarantee of a suitable housing offer for all homeless households.

Priority access to social housing for homeless households is better protected in Scotland than in either England or Wales (Principle 3a). But in none of the jurisdictions has intentionality been abolished, or the definition of intentionality been narrowed to match the specific ‘mischief’ that it was intended to deal with (Principle 3b). The problem of local connection as a barrier to assistance has not been addressed in any of the three countries (Principle 4).

The protections for those who exhaust their statutory entitlements under the homelessness legislation are weak across all three countries at present (Principle 5). An entitlement to housing support is already established in Scotland, but not in the other two countries (Principle 6(a)).

There has been some recent strengthening of the responsibilities of other public bodies in England and Wales, though these do not go far enough (Principle 6(b)).97 Inspection and regulation arrangements are stronger in Scotland than in either of the other two countries at present (Principle 7). On reviews and appeals (Principle 8), homeless applicants are able to access a wide scale reconsideration of their factual circumstances in all three countries of Great Britain, but not by an independent body. Early advice is available, but funding cuts to housing advice and legal aid means that in practice it can be very difficult, or sometimes impossible, to obtain.

All three countries have considerable work to do to satisfy both Principles 9 and 10, although Wales has provided training for the local authority workforce following the passage of The Housing (Wales) Act (2014).

There are a number of factors that critically affect the functioning of even the most ideal of statutory homelessness systems. Below are the most important factors, each of which requires wider governmental attention. However, the absence of one or more of these factors should not be considered a bar to making progress with the legislative agenda. Previous experience indicates that while an absence of wider structural reform can hamper progress on homelessness, marked success can be achieved in even the most difficult contexts.

First, international comparative evidence indicates that a strong policy direction and strategic grip from central government is required to enforce national minimum standards and to enable best practice to be scaled up. In this respect, it is vital in England, Scotland and Wales, that legal reform is part of a focused and cross-government plan to end homelessness.

Second, and perhaps most obviously, the success of an ideal statutory framework relies heavily on a sufficient supply of decent, affordable housing, accessible to those on low incomes, and located in the places that they need to live. Chapter 11, ‘Housing solutions’, specifically addresses this point, with detailed analysis of the housing supply requirements of homeless households. Chapter 11 also describes the reforms necessary to ensure the private rented sector becomes a more secure, affordable and higher quality option for people at risk of, or who have experienced, homelessness.

Third, the benefit system is crucial in allowing local authorities to make suitable offers of accommodation under the statutory system. Chapter 10, ‘Making welfare work’, details the changes required to ensure that housing allowances meet the actual rents being charged to low income households in the private rented sector.

Fourth, if local authorities are to continue to be charged with statutory and strategic duties to address homelessness, they must be appropriately resourced to deliver these responsibilities.

This chapter envisages a new homelessness system that melds the best from England, Scotland and Wales. This ideal contains the following features:

With wider contextual factors taken into account, this is a framework of law that is the natural extension to the post Housing (Homeless Persons) Act (1977) settlement throughout Great Britain. It is a bold vision, but at its heart is about completing the safety net that already exists for some.

Every lever possible at our disposal in driving down homelessness must be seized. The law is one such crucial lever.

As already noted in this chapter, the table of summary recommendations for national governments reflect agreed principles, but are entirely written by Crisis.

England/Westminster

Scotland

Wales

In simple terms they will go up. New Crisis research published today conducted by Heriot--Watt Un...

Private renting is increasingly the biggest solution to homelessness and yet, for some time now,...