The scale of homelessness across Great Britain is unacceptable. This chapter shows that if current policy choices remain in place for the next 25 years the situation will get much worse. This chapter sets out the significant differences across the three nations and obvious policy choices that could reverse the increase in homelessness.

Before a long-term plan for ending homelessness can be established the true extent of the problem and its likely trends over time must be understood. To this end we commissioned Heriot-Watt University to collate the best available data on trends and experiences of homelessness. We also asked the researchers to provide the known impacts of policy choices on numbers of homeless people.

This chapter draws heavily on the results of this two-stage study. Resulting data shows that homelessness will continue to rise across Great Britain unless different policy choices are made.

One key reason for commissioning the study was the absence of sufficiently reliable measures of homelessness prevalence and of the demand for homelessness services. Rough sleeping data is problematic across Great Britain. In England, government figures are based on an estimate, with only 15 per cent of local authorities actually counting people on the streets.

In Wales there are similar concerns about data that the Welsh Government describes as ‘essentially a snapshot estimate and can only provide a very broad indication of rough sleeping levels’.

In Scotland, data comes from the number of people presenting to the local authority who report having slept rough the night before, or in the previous three months. This has the obvious drawback that those not presenting to local councils will not be counted. Estimates of those who do not present range from 30 per cent 4 to 61 per cent.

Much of the data reported about homelessness is actually a measure of the supply of help available to people, rather than the levels of demand for that help. For example, the numbers of people counted as using hostels and night shelters in England in 2016 was 35,727; this represents a 2% decrease on the previous year, yet 66% of accommodation projects had to turn people away because they are full.

Similarly, data for hostel and night shelter use in Scotland and Wales are only routinely collected as a sub-set of figures about the use of temporary accommodation for statutory homeless households. They are not a complete picture of provision of this emergency accommodation or demand for it.

Statutory homelessness acceptances data is often used to report levels of homelessness. This is problematic in a number of ways.

First, data about those rehoused via the statutory systems across Great Britain is a measure of the households whose homelessness has been resolved, or is in the process of resolution. It is not a measure of the actual numbers of homeless people.

Second, as with hostel data, these numbers are increasingly a measure of supply of the assistance that local authorities have resources to deliver. This issue is particularly pronounced in England. Here local authorities themselves cast doubt over the use of statutory acceptance figures as a measure of demand for their services.

In England and Wales, the use of statutory homelessness figures carries a significant problem. Non-priority homeless households may not be captured if applications are never made, or people don’t approach local authorities for help, knowing that they will be a non-priority case.

In Scotland, the official homelessness statistics are by far the most robust of the three nations (as detailed in Chapter 14 ‘Homelessness data’). However, they are still not reliable as a measure of homelessness prevalence or demand, or of the different ways people experience the problem.

Finally, across Great Britain no regular and reliable data is available for ‘hidden’ homeless populations. This includes people sofa surfing, people in cars, tents, squats, public transport, or 'beds in sheds'.

To present a more reliable and comprehensive estimate of homelessness across Great Britain, a model of core homelessness has been developed. Core homelessness refers to the population of people experiencing the most acute forms of homelessness, or living in short-term emergency and unsuitable accommodation. Below details each component group of homeless people.

*For the projections data shown in this chapter, these groups of homeless people are presented as ‘other’.

To estimate levels of core homelessness in 2011 and 2016 across England, Scotland and Wales, a new model was built by Heriot-Watt University. It used secondary data sources including panel and household surveys, alongside statutory statistics and academic studies. Given the uncertainties and inconsistencies of some data sources, a low, mid and high range was produced. All figures presented below reflect the mid-range.

Table 5.2 below details the core homeless population at any one point in time across Great Britain in 20111 and 2016. In 2016, core homelessness in Great Britain stood at 158,400 households (142,000 in England, 11,000 in Scotland, 5,400 in Wales).

The largest groups of core homeless households are those who are sofa surfing (67,000), those staying in hostels, refuges and shelters (41,700) and those in unsuitable temporary accommodation (19,300).

While overall core homelessness increased between 2011 and 2016, it is worth noting that the hostel, refuge and night shelter group actually decreased. This is mostly due to the provision of this kind of homelessness assistance decreasing over this period, rather than the demand for it falling.

Many of these core homeless households are single adults of working age, although significant numbers of families with children are also contained within the groups. The research estimates that the actual number of core homeless people is 236,000. This includes 57,000 family households with 82,000 adults and 50,000 children.

Core homelessness increased by 33 per cent overall between 2011 and 2016. The largest increase is within unsuitable temporary accommodation in England, which more than doubled in this period. It is also of note that while overall levels increased in England and Wales, Scottish core homelessness fell slightly. National and GB-wide future analyses are shown in the chapter on the full PDF of the plan.

To forecast future levels of homelessness, the following two assumptions have been made. Current and planned policies in welfare and other major policy areas will continue and relatively benign conditions will prevail in the wider economy and labour market.

The model that sits behind these projections uses 15 inter-dependent variables, including relative poverty, eviction rates, homelessness applications, etc. The model also takes into account the relative success of the different national legislative arrangements for statutory homelessness.

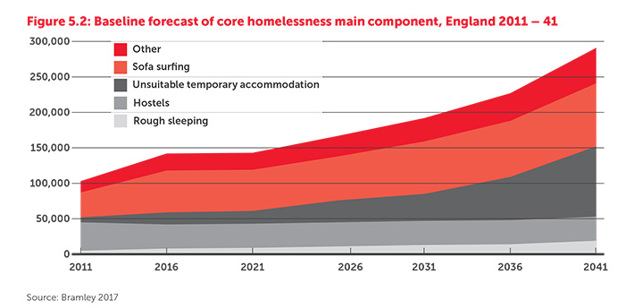

Core homelessness in Great Britain is forecast to continue to grow over the next 25 years (see figure 5.1 below). Although in the medium term the rate of increase is tempered by a predicted correction in the affordability of the housing market. By 2041 there are predicted large increases in homelessness, largely driven by increases in England.

Across England, Scotland and Wales there are marked differences in projected levels of homelessness in the coming years, but also in the relative size of the different core homeless groups

England

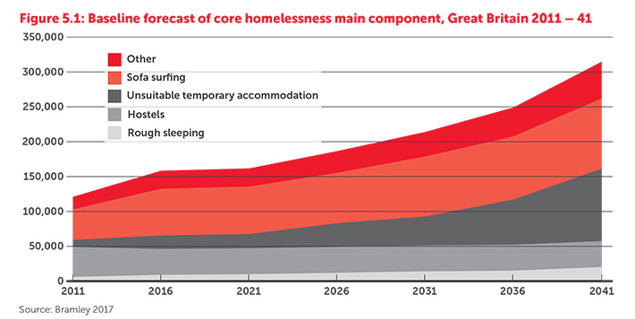

Projections for England (see figure 5.2 below) show an initial pause followed by an accelerated increase towards the end of the forecasted period. This is driven by a constant increase in rough sleeping, and by a dramatic rise in unsuitable temporary accommodation in London. Housing and welfare policies have a continued detrimental impact, as does the absence of targeted and effective measures to address rough sleeping.

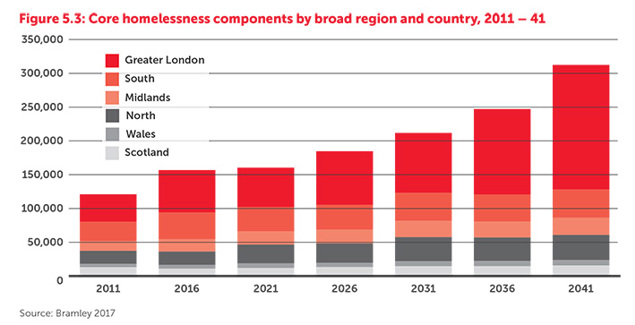

Figure 5.3 below demonstrates the significant variations in core homelessness growth by English region and each nation. By 2041, 184,400 households in Greater London are homeless, compared to 104,300 for the rest of Great Britain. This is because of the scarcity of affordable housing in the capital. Having sufficient affordable housing is a way to guard against homelessness, and a resource to deal with it once it occurs.

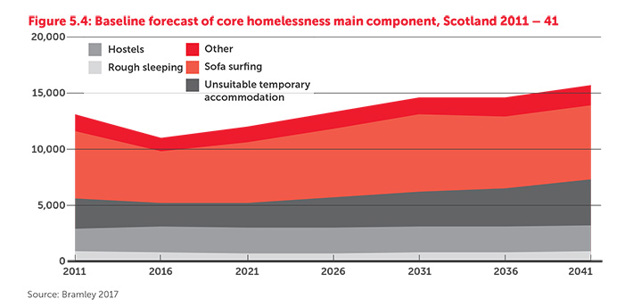

Scotland

In Scotland (see figure 5.4 below) , all groups of homeless people remain constant or fall, up until 2021. Then slight growth is predicted to 15,700 households by 2041. The relative success in housing supply and affordability is of note in Scotland. However, welfare reform measures and wider poverty continue to inhibit progress, as does the issue of statutory homeless people stuck in unsuitable temporary accommodation.

A new set of policies to tackle rough sleeping, temporary accommodation and longer term solutions to homelessness are currently being considered by the Homelessness and Rough Sleeping Action Group in Scotland. Proposals on how to end rough sleeping in Scotland have now been made to the Scottish Government. All of the recommendations have been accepted in principle. Once agreed, and if adopted by the Scottish Government, these can be used to reforecast the data.

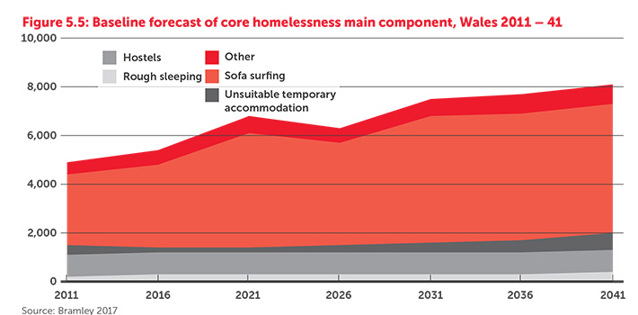

Wales

In Wales (see figure 5.5 below), core homelessness is set to rise significantly, with a number of factors contributing. General economic performance is predicted to be weaker than the UK average during the forecasted period, and housing market pressures within England are set to ‘spill over into Wales’.

These data forecast ongoing success in homelessness prevention, following the introduction of new duties under The Housing (Wales) Act 2014. However, it is clear that without a wider strategy to capture those failed by the statutory system, and broader structural factors, these changes will be insufficient.

5.6 The potential impact of different policy choices

The factors identified as drivers of core homelessness include: poverty, which is closely aligned with sufficiency in social security and therefore welfare reform measures, and homelessness prevention. This includes the ability of local authorities to employ prevention measures that successfully negate the need for rehousing (and use of unsuitable temporary accommodation).

Having identified these areas, the forecasting model was used to project a range of ‘what if’ scenarios that reflect modest changes to some relevant policy areas (see figure 5.6 below).

*FIGURE 5.6 SUMMARY OF SCENARIOS AND IMPACT ON CORE HOMEELSSNESS IN GREAT BRITAIN*

The first scenario tested was a policy choice not to go ahead with the planned welfare cuts for the period 2016-21, or any similar such cuts in the 2020s. The model suggests this has a clear and positive impact, with a 42 per cent reduction by 2041 compared to the baseline projection.

The second scenario tested was a substantial increase in new housing supply of 60 per cent, including social/ affordable units. This alters the core homelessness forecast substantially. It involves a 15 per cent reduction against the baseline by 2036, and a particular reduction in rough sleeping and unsuitable temporary accommodation in London and the South East of England.

The third scenario presents the idea of ‘maximal prevention’,21 which involves all local authorities in Great Britain matching the activities of those with the most meaningful and successful prevention activities. This again has a positive impact on future projections, with a large reduction of 25 per cent against the baseline by 2026.

These are a snapshot of the singular impacts of different policy choices, rather than a comprehensive and aggregated solutions framework. However, they reinforce the conclusion of Chapter 2 on public policy and homelessness that current and future levels of homelessness are a reflection of political choices

In the process of considering and gathering improved data about the most acute core elements of homelessness in Great Britain, Heriot-Watt also built a model of those who are considered to be in the wider homelessness group. This includes a range of situations including other statutory homeless households who have been housed in suitable forms of temporary accommodation; and people at risk of core and statutory homelessness.

Wider homelessness:

Those within the wider homelessness group are a broader group of people, experiencing insecure or poor housing. They may have recently experienced core homelessness, or are statutorily homeless and have been rehoused in suitable temporary accommodation including social housing. Statutory households still in emergency accommodation or unsuitable (such as bed and breakfasts) are counted within the core homeless group.

It is important to acknowledge this wider group, and also the cross over in the definition of homelessness ended between core and at risk homelessness. In reality the two groups will cross over in a number of ways and some households in the wider homeless group, are more at risk of experiencing core homelessness than others. For the purposes of definitions four and five, we have identified that 87,892 households in wider homelessness are at risk. It remains important, however, to identify and highlight the most acute forms of homelessness to design strategies for tackling the problem in its most pernicious forms.

Although many people are protected by the homelessness systems and entitlements across Great Britain, homelessness remains a devastating problem, set to rise further if current policy choices are continued. We are on course to witness a catastrophic rise in the most acute and damaging forms of homelessness.

The modelling of different policy choices against these projections, does however offer a source of hope and inspiration. There is clear evidence that short and long-term policy choices can make a substantial difference to homelessness projections. Consequently, it is imperative to advocate evidence-based choices that will make the greatest difference. The following chapters do that.

In simple terms they will go up. New Crisis research published today conducted by Heriot--Watt Un...

Private renting is increasingly the biggest solution to homelessness and yet, for some time now,...