Thomas Parker and the Tragedy of Vagrancy Law

04.02.2020

On the night of May 31, 1933, Mr. Thomas Parker took shelter to sleep under a steam truck near the village of Coleshill, outside Birmingham. Thirty-four years old, Parker was destitute and homeless, having just left the Bagthorpe workhouse in Nottingham days before. He was promptly arrested for sleeping out and for ‘not having any visible means of subsistence’ under the Vagrancy Act 1824, which makes rough sleeping and begging illegal in England and Wales. The next night he was a convict serving a 14-day sentence with hard labour at Winson Green prison.

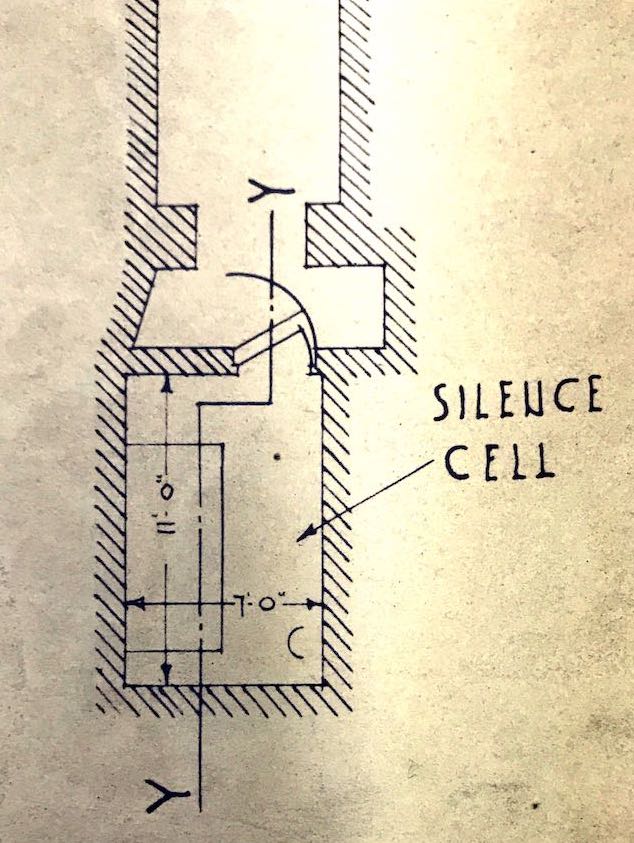

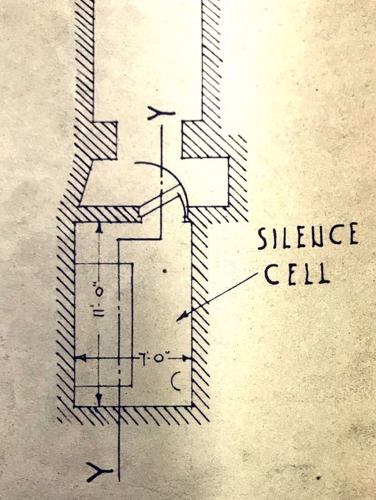

The next morning, June 2, he was found to be ‘insolent and disobedient’ in the drill yard and was brought before the prison’s acting governor in the adjudication room at about 11.20 am. His immediate punishment was three days in the special ‘silence’ punishment cell, with a diet of only bread and water. What happened in the next 20 minutes would become a source of national controversy and would change how the rough-sleeping offence would be enforced into the 21st century.

From the office where his punishment was summarily given to the silence cell itself was a distance of 64 yards – down a steep flight of stairs, along a gangway and through a double door – to a cell no bigger than a parking space. As two guards pulled him into the cell at 11.25 am he was losing consciousness from a brain haemorrhage, caused by a vicious blow to the right side of his head. Fifteen minutes later he would be found dead, his six-foot body curled up and his head resting on the cement curb of the prisoner’s sleeping platform.

[Photographs and a technical drawings were prepared by the Coroner to be presented as evidence to the jury at the inquest. They include the ‘silence cell’ Thomas Parker died in (fig 1 and 2). Note the very crude ink sketch (fig 1) on the photograph made to illustrate the position of Parker’s head.]

The Birmingham coroner, Dr W.H. Davison, opened an inquest into Parker’s death the next day and, after issuing a burial certificate for the body, promptly adjourned. Time was needed, he said, to ascertain the full facts and to arrange for the inquest to be moved to the prison on June 13. This highly unusual move reflected the fact that Thomas Parker was not only a penniless ‘vagrant’ but also an ex-soldier, formerly with the Grenadier Guards.

The possibility of being blamed for the death of a homeless ex-Guardsman did not just unsettle prison officials. The Home Office dispatched the famous pathologist Sir Bernard Spilsbury to Birmingham. Spilsbury reviewed the coroner’s work and testified as a witness at the inquest, drawing in part on his examination of Parker’s brain, which had been removed and preserved before the burial.

How exactly Parker died that morning remains a mystery. What is certain is that the benefit of any doubt was given to prison staff; they were not at fault. The final verdict, read out on June 14, was ‘accidental death’, caused by ‘falling down the stairs’.

With the prison staff absolved of blame, attention was turned to the law itself. The ‘Soldier MP’, Brigadier-General Edward Spears, Conservative MP for Carlisle, would give voice to the disgust many felt at Parker’s death. A formidable man, Spears had attended the inquest and went on to rail against the Vagrancy Act both in Parliament and in the press. ‘He was in prison,’ Spears stated to the House of Commons on June 22, ‘because he had lain down to sleep on the soil of the country he had risked his life to defend.’

The result was the Vagrancy Act 1935, which passed with all-party support. The Act amended the Vagrancy Act 1824, placing severe restrictions on how the rough-sleeping offence could be enforced. The reforms seemed custom made to protect people in the circumstances that Thomas Parker found himself in. In order to make out an offence, there had to be free shelter space available and accessible, and the rough sleeper would have to refuse to take it. Even today, police officers must satisfy this requirement in order to make an arrest for rough sleeping. Perhaps even more significantly, the offence ingredient of ‘not having any visible means of subsistence’ was removed, repealing a core purpose of vagrancy law: to punish those who were visibly poor.

However, continued use of the Vagrancy Act today makes a mockery of the 1935 reforms designed to protect rough sleepers. While rough sleeping alone is far less prosecuted today because of the 1935 Act, it nonetheless remains a criminal offence, and this fact is cited informally to ‘move on’ people who are sleeping rough.

Much more troubling is how the current begging offence is used to target rough sleepers in a way that makes being visibly poor a crime. And unlike rough sleeping, the offence of begging is actively enforced: between 2005 and 2015 there were more than 15 000 convictions for begging, resulting in more than a million pounds in fines. The homeless charity Crisis recognizes this threat to rough sleepers in their campaign to have the Act repealed. As they have documented in their research, when a rough sleeper protested to a police officer who said he was begging, the officer responded, ‘You don’t have to talk to people or have a card or a cup. Basically if I walk along and I see you placed to beg, I think you’re there to receive money or food – you’re begging. You’re committing an offence.’

This is a perfect example of how the archaic wording of the begging offence – ‘to beg or gather alms’ – is so broad and vague as to capture the very presence of a rough sleeper on the pavement. Someone who is visibly destitute is automatically assumed to be ‘placed to beg’. The crime of not having ‘any visible means’ is alive and is being enforced today through the begging offence.

And while rough sleepers are no longer sent to prison (convictions are now punished via fines), sleeping rough is nonetheless a slow death sentence. Public space is a punishment cell for poor people who are branded as criminals by the vagrancy law, a space where hundreds of rough sleepers died last year, many in silence and alone. Armed Forces members, to whom the Prime Minister expressed ‘personal gratitude’ in his Christmas message, remain disproportionately at risk for becoming homeless.

It has been almost a century since Thomas Parker was buried in a common grave at Witton cemetery in Birmingham. His death made visible the cruel intent of the Vagrancy Act that remains enforced today. Will the new government put an end to this dark and brutal law?

Joe Hermer is a Sociology Professor at the University of Toronto Scarborough. He is the author of Policing Compassion: Begging, Law and Power in Public Spaces by Hart Publishing.

[ Twitter: @joehermer]

Images reproduced with the permission of the Library of Birmingham.

For media enquiries:

E: media@crisis.org.uk

T: 020 7426 3880

For general enquiries:

E: enquiries@crisis.org.uk

T: 0300 636 1967